The first major exhibition of Pierre Bonnard’s work in the last 20 years will be held in the Tate Modern (UK) next January. The exhibition Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory is organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen and Kunstforum Wien. It will introduce Pierre Bonnard to new generations and surprise those who think they already know the artist. The display focuses on Bonnard’s work from 1912 when he concentrated mainly on color until his death in 1947. Limiting his oeuvre solely within the Modern era, the exhibition will try to rethink his position in the history of art, as a 20th-century artist, ignoring his grand input from the 1890s as a founder of the symbolist Nabis

group.

Born 1867, Bonnard was one of the greatest colourists of the early 20th century. His successful career as a painter and printmaker began when he designed a poster for a Reims champagne manufacturer in 1889. When Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec saw it, he was so impressed that decided to start designing posters of his own.

Bonnard shared a studio at the foot of Montmartre with Édouard Vuillard and Maurice Denis around that time. The young artists decided to form a secret confraternity called the Nabis (from the Hebrew word meaning ‘prophets'), along with Paul Sérusier and others. Members of the group were all deeply influenced by Paul Gauguin and saw painting as an illusionistic window onto nature. They also believed in the virtues of craftsmanship and held that art should be an integral part of daily life. That’s why the Nabis created the variety of beautiful objects like theatre sets, posters, costumes, tapestries, fans and decorative screens, as well as paintings.

Influenced by Paul Gauguin and Japanese art, work of Bonnard at that time is generally characterised by its flat, decorative quality and emphatic stylization. Decorative features actually remained present in his work during the whole 20th century.

Bonnard shared a studio at the foot of Montmartre with Édouard Vuillard and Maurice Denis around that time. The young artists decided to form a secret confraternity called the Nabis (from the Hebrew word meaning ‘prophets'), along with Paul Sérusier and others. Members of the group were all deeply influenced by Paul Gauguin and saw painting as an illusionistic window onto nature. They also believed in the virtues of craftsmanship and held that art should be an integral part of daily life. That’s why the Nabis created the variety of beautiful objects like theatre sets, posters, costumes, tapestries, fans and decorative screens, as well as paintings.

Influenced by Paul Gauguin and Japanese art, work of Bonnard at that time is generally characterised by its flat, decorative quality and emphatic stylization. Decorative features actually remained present in his work during the whole 20th century.

Even though Bonnard’s works are so vivid and lifelike, as if he captured the spirit of a moment en plein air, Bonnard did not paint directly on the spot, preferring instead to make drawings, sketches and colour notes and then working up his paintings in the studio through the unique handling of colour and innovative sense of composition. He hardly believed that painters were capable of tackling the motif directly, declaring, "It is not a matter of painting life. It’s a matter of giving life to painting".

Like his close friend Henri Matisse, the Fauvist, he used colour and decoration as the essential qualities of his art. Bonnard admired not only Japanese prints and screens but also Persian and Indian miniatures. They inspired him to capture something of the iridescent multiplicity and to orchestrate brilliantly near and far views of his own landscapes filling them with vibrant notes of Indian yellow, ultramarine, emerald green, creamy white and deep, reddish purple.

Like his close friend Henri Matisse, the Fauvist, he used colour and decoration as the essential qualities of his art. Bonnard admired not only Japanese prints and screens but also Persian and Indian miniatures. They inspired him to capture something of the iridescent multiplicity and to orchestrate brilliantly near and far views of his own landscapes filling them with vibrant notes of Indian yellow, ultramarine, emerald green, creamy white and deep, reddish purple.

Summer

1917, 260×340 cm

The exhibition Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory concentrates on Bonnard’s work from 1912, when colour became his dominant concern. It will present beautiful landscapes and intimate domestic scenes which even made art historians develop a special term 'intimism' for them.

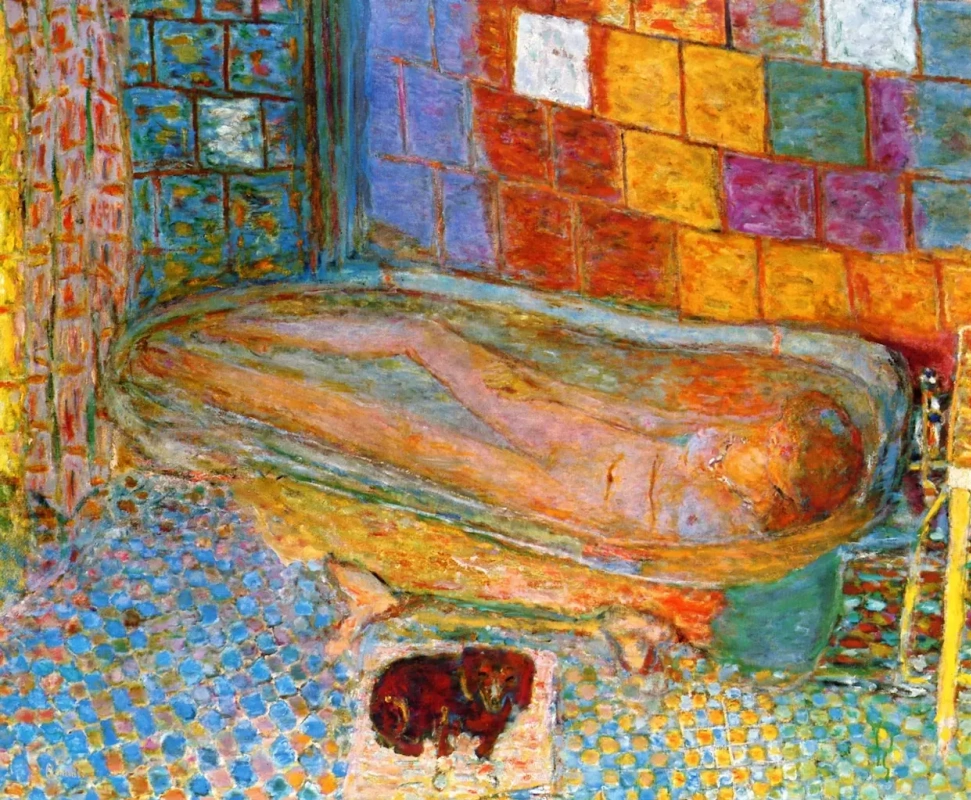

Much of Bonnard’s output in the last half of his life is a diary of intimate domesticity. His beloved wife Marthe appears in most of these pictures either dressed up and sitting at the table, drinking coffee, or in a chair with a dog at leisure, or naked, combing her hair, looking in the mirror, or taking bath. Sometimes, she is the principal subject, but more often she appears almost as part of the furniture, as if dissolved in its hues. This is no accident — not only Bonnard’s art but his whole life came to be dominated by her.

Much of Bonnard’s output in the last half of his life is a diary of intimate domesticity. His beloved wife Marthe appears in most of these pictures either dressed up and sitting at the table, drinking coffee, or in a chair with a dog at leisure, or naked, combing her hair, looking in the mirror, or taking bath. Sometimes, she is the principal subject, but more often she appears almost as part of the furniture, as if dissolved in its hues. This is no accident — not only Bonnard’s art but his whole life came to be dominated by her.

Coffee

1915, 73×106.4 cm

Marthe de Meligny was a very strange person. When she first met Pierre in Paris, she told him that she was 16 years old when, in fact, she was already 24 at that time. She also lied about her name, which was in fact Maria Boursin. Probably she thought it was too unfashionable for a man belonging to a social class higher than her poor family’s — her father was a carpenter from Bourges. Anyways, Bonnard did not know her real name and age until he married her in… 30 years. Their relationship was not simple. Pierre Bonnard had several love affairs with other women, and Marthe de Meligny was definitely plagued by concerns about her health.

Some of Marthe’s concerns required various dietary regimens, others lead to her spending much time plunged in a bath. That’s why Bonnard created so many paintings showing Marthe either taking bath or getting out of it. She also became increasingly reclusive, and she may even have suffered from some psychiatric disorder. What we know for sure is that in 1930, four years after the couple had bought a house in the south of France, Pierre Bonnard wrote to a friend: "For quite some time now I have been living a very secluded life as Marthe has become completely anti-social and I am obliged to avoid all contact with other people".

Nude in the Bath and Small Dog

1941, 121×151 cm

Marthe disapproved of visits from fellow artists to their home, and friends referred to her as a demon or a ‘tormenting sprite'.

Bonnard, however, seems to have borne all her weirds with a resigned fatalism. His intimate paintings hardly ever hint at his difficult home life. Marthe’s portraits are always full of light and radiant color. Her body never ages and she always appears in her husband’s later paintings as a young woman. Actually, Marthe was the catalyst for Bonnard’s studies on form and color.

Whatever issues Bonnard had with his wife, we see in his intimistic paintings deeply intimate and adoring images of the relationship between husband and wife and artist and his muse.

Bonnard, however, seems to have borne all her weirds with a resigned fatalism. His intimate paintings hardly ever hint at his difficult home life. Marthe’s portraits are always full of light and radiant color. Her body never ages and she always appears in her husband’s later paintings as a young woman. Actually, Marthe was the catalyst for Bonnard’s studies on form and color.

Whatever issues Bonnard had with his wife, we see in his intimistic paintings deeply intimate and adoring images of the relationship between husband and wife and artist and his muse.

Woman undresses

1930

The coming exhibition will also give the insights into Bonnard’s response to the First and Second World Wars, although very little is known about it. Curators brought up two rarely seen works which will go on display together in the UK for the first time since they were painted. A Village in Ruins near Ham (1917) shows desolation and misery of the First World War while The Fourteenth of July (1918) shows national celebration.

A Village in Ruins near Ham

1917, 63×85 cm

Matthew Gale, curator of the exhibition and the Head of Displays at Tate Modern says that Bonnard’s painting A Village in Ruins near Ham (above) was produced as part of a system of taking artists to the front "to capture a sense of the destruction and the suffering of the armed forces".

He continues, "You can see that Bonnard is trying to catch an instant vision mediated through his studio practice into what is a pretty unusual painting for him."

He continues, "You can see that Bonnard is trying to catch an instant vision mediated through his studio practice into what is a pretty unusual painting for him."

The Fourteenth of July 1918 (Armistice)

1918, 59.5×85.3 cm

The 14th of July (above) captures nocturnal Bastille Day celebrations in 1918. Mathew Gale says that its carousel in the background and "a figure who looks a bit like Delacroix’s Liberty on the Barricades, surging up, [give us] a sense of the revival of peace and its return to France after the traumatic experience of the First World War".

Mr. Gale emphasizes that the exhibition is aimed at acknowledgement of Bonnard’s awareness of what was going on in the world around him despite his domestic seclusion and underlines his efforts in bringing this knowledge into his art. He claims that this fact has hitherto been rather overlooked.

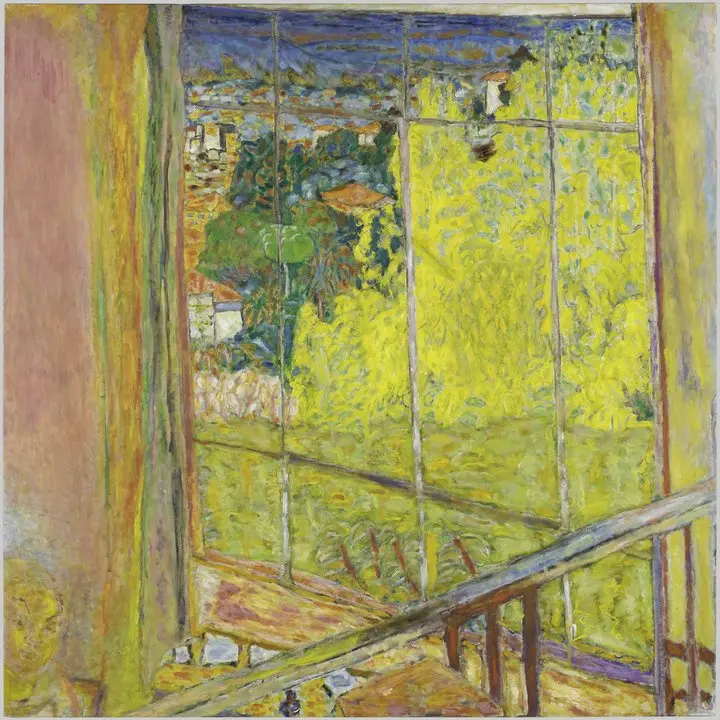

The increasingly austere and dangerous years of the German Occupation in France during the Second World War, Bonnard, who was then in his 60s, has spent in his house at Le Cannet, above Cannes. Being anxious of invasion and faced with the shortages of fuel, petrol, food, and art supplies, he was essentially trapped in the house and produced primarily landscapes in that period.

Helen O’Malley, an Assistant Curator, claims that Bonnard "was pushing into abstraction in quite a heavy way" during the Second World War and that it "was linked to the fact that it was a difficult time for everyone, so his work was becoming increasingly emotional and distorted." All the more, it was the time when Marthe died and Bonnard himself went into hospital for a period.

Mr. Gale emphasizes that the exhibition is aimed at acknowledgement of Bonnard’s awareness of what was going on in the world around him despite his domestic seclusion and underlines his efforts in bringing this knowledge into his art. He claims that this fact has hitherto been rather overlooked.

The increasingly austere and dangerous years of the German Occupation in France during the Second World War, Bonnard, who was then in his 60s, has spent in his house at Le Cannet, above Cannes. Being anxious of invasion and faced with the shortages of fuel, petrol, food, and art supplies, he was essentially trapped in the house and produced primarily landscapes in that period.

Helen O’Malley, an Assistant Curator, claims that Bonnard "was pushing into abstraction in quite a heavy way" during the Second World War and that it "was linked to the fact that it was a difficult time for everyone, so his work was becoming increasingly emotional and distorted." All the more, it was the time when Marthe died and Bonnard himself went into hospital for a period.

View of Le Cannet

1942

Bonnard’s self-portraits completed at the end of his life (bellow) echoes his growing sense of personal fragility and impending mortality.

In a post-Cubist atmosphere some art critics dismissed Bonnard as old-fashioned and irrelevant. Their attacks had disturbed the painter and may have prompted the series of probing late self-portraits. In profound concentration, with a permanent desire to understand and fulfil himself as an artist, Bonnard’s self-portraits defied the climate of the times.

In 1930-s, Bonnard wrote in a letter to his nephew Charles Terrasse: "I am working a lot, immersed more and more deeply in this outdated passion for painting. Perhaps with a few others, I am one of its last survivors".

In a post-Cubist atmosphere some art critics dismissed Bonnard as old-fashioned and irrelevant. Their attacks had disturbed the painter and may have prompted the series of probing late self-portraits. In profound concentration, with a permanent desire to understand and fulfil himself as an artist, Bonnard’s self-portraits defied the climate of the times.

In 1930-s, Bonnard wrote in a letter to his nephew Charles Terrasse: "I am working a lot, immersed more and more deeply in this outdated passion for painting. Perhaps with a few others, I am one of its last survivors".

The exhibition Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory will emphasise Bonnard as a prominent 20th century colourist and painter who — like his contemporary and close friend Henri Matisse — greatly influenced modern painting and had a profound impact on later artists like Mark Rothko and Patrick Heron.

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory will be at Tate Modern from 23 January until 6 May 2019. After Tate Modern the exhibition will travel to Copenhagen and Vienna. It is curated at Tate Modern by Matthew Gale, Head of Displays, with Helen O’Malley and Juliette Rizzi, Assistant Curators.

Written on materials of press release of tate.org.uk, The Art Newspaper, Art Gallery of New South Whales, The Guardian, worldsbestpaintings.net. Title illustration: Pierre Bonnard, The Studio with Mimosas, 1939−46, Musee National d’art Moderne — Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Художники, упоминаемые в статье

Рекомендуем почитать

2 мин.Женщина нашла у себя дома картину да Винчи4 мин.Париж: Брак с птицами1 мин.Натюрморт с цветами1 мин.Открытие юбилейной выставки Дмитрия Санджиева в доме-музее Николая Седнина.

19 мин.Интервью с художником Алексеем Смоловиком. Журнал "Вода живая" 12(декабрь)2024Интервью с художником Алексеем Смоловиком. Журнал "Вода живая" 12(декабрь) 2024Интервью с художником Алексеем Смоловиком. Журнал "Вода живая" 12(декабрь) 2024Интервью с художником Алексеем Смоловиком. Журнал "Вода живая" 12 (декабрь) 2024