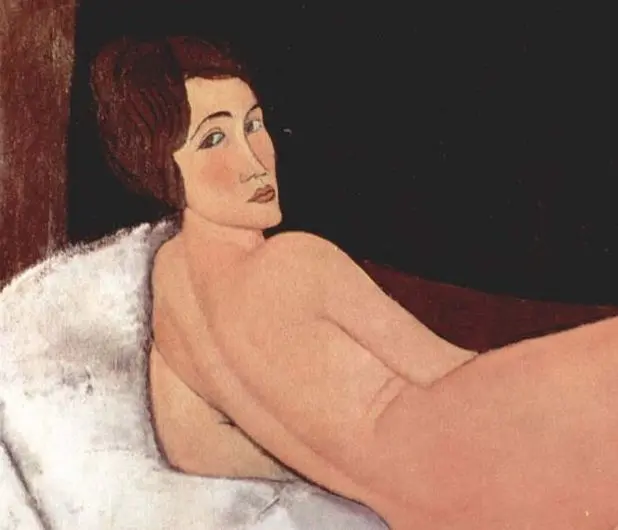

Curators want to shine new light on an artist, who is sometimes better known for his dissolute lifestyle, as well as to show there is far more to Modigliani than portraits of long-faced people with blank almond eyes.

A tubercular alcoholic, addicted to women, hash and ether, unrecognised, impoverished and dead at 35 with the last painting still wet on the canvas: Amedeo Modigliani (1884−1920) is a Romantic throwback in 20th-century art. Even his nickname, Modi, is a pun on the peintre maudit, the accursed painter, a phrase coined half a century before he was born. Modigliani met and fraternised with artists including Picasso, Derain, Juan Gris, and Diego Rivera, with whom he shared a studio. For all this time, Modigliani was searching for his own style.

Left: Modigliani in his studio, photographed by Paul Guillaume, c. 1915. Photograph: © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée de l’Orangerie)

Sculpture played a significant role in simplifying forms. Modigliani’s real ambition, as he once said, was to work in stone, and there’s a fixity and incision to all his painted portraits.

Despite his poverty and lack of commercial success, dozens of artists attended his funeral in Paris, and the exhibition reflects his cosmopolitan connections and friendships. Portraits include his fellow artist Pablo Picasso — shown as a bit of a bruiser, with a shock of dark hair — the painter Juan Gris, and a playful portrait of his friend Jean Cocteau, which Ireson said came close to caricature and was disliked by the writer.

Left: Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jean Cocteau (1917). In a long lease at the Art Museum of Priston University (USA)

The exhibition includes several portraits of one of his more flamboyant friends, Beatrice Hastings, who worked as a critic, poet and journalist under at least 30 pseudonyms, and whose many other lovers included the writers Katherine Mansfield and Wyndham Lewis. She recalled their first meeting, "Hashish and brandy. Not at all impressed … He looked ugly, ferocious, greedy."

The show ends with a row of portraits of his last lover, Jeanne Hebuterne, though there isn’t a trace of tragedy on their sinuous arrangements of ovoid forms. While it’s surprising Modigliani was even able to hold a paintbrush by this point, he seems to have been aiming, as in much of his work, for a quasi-classical feeling of serenity.

Based on materials www.theguardian.com, www.telegraph.co.uk, official site of Tate Modern