The bold flairs of calligraphic script shout for attention, while elegant flourishes of cursive sashay across the page. Free-spirited scribbled letters trip over each other, and distinctive dashes help direct traffic. Some crossed t’s and dotted i’s stand alert, and others slump or sway into their neighbors. Every message brims with the personality of the artist at the moment of interplay between hand, eye, mind, pen, and paper.

While in many cases graphology cements what we already know about these heavily researched personalities, it also surfaces curious and eccentric details—like van Gogh’s tendency to leave his Ts uncrossed.

With this in mind, writing a letter can be an artistic act. In carefully composed letters, artists choose the penmanship style, utensils, and paper that will convey their creative inclinations."

Mary Savig, the curator of manuscripts

at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

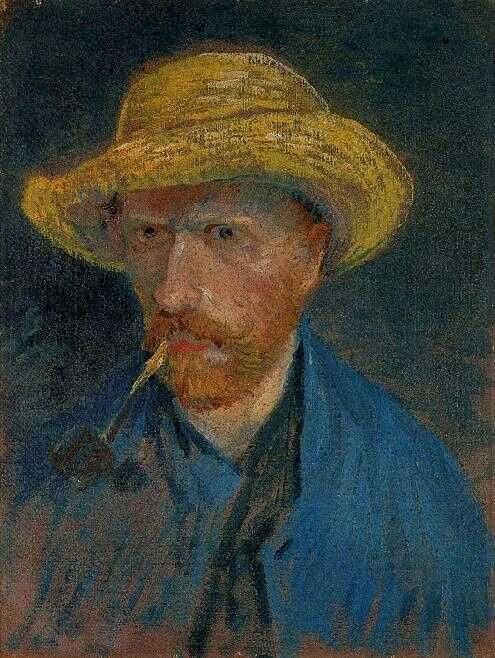

Vincent van Gogh

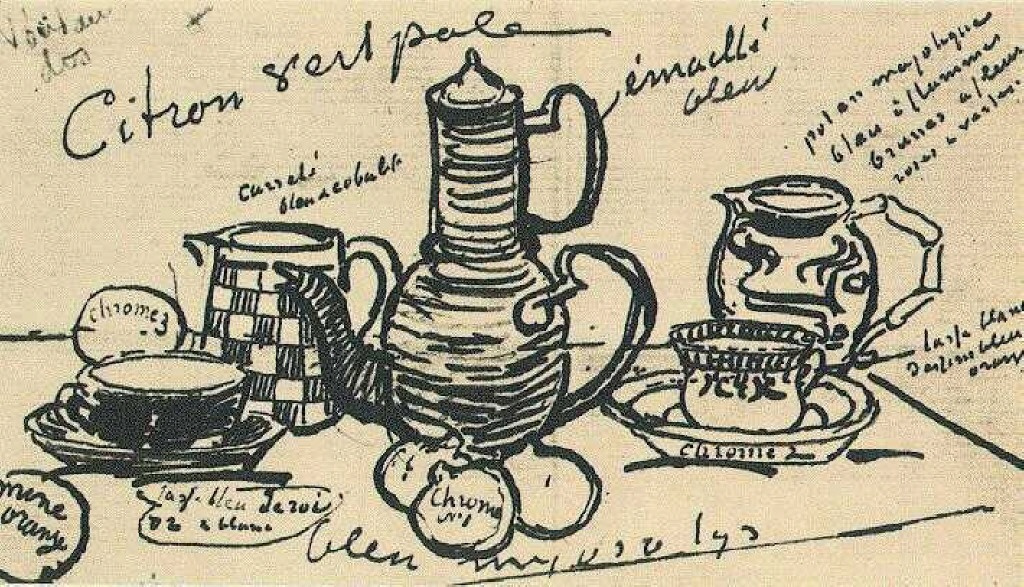

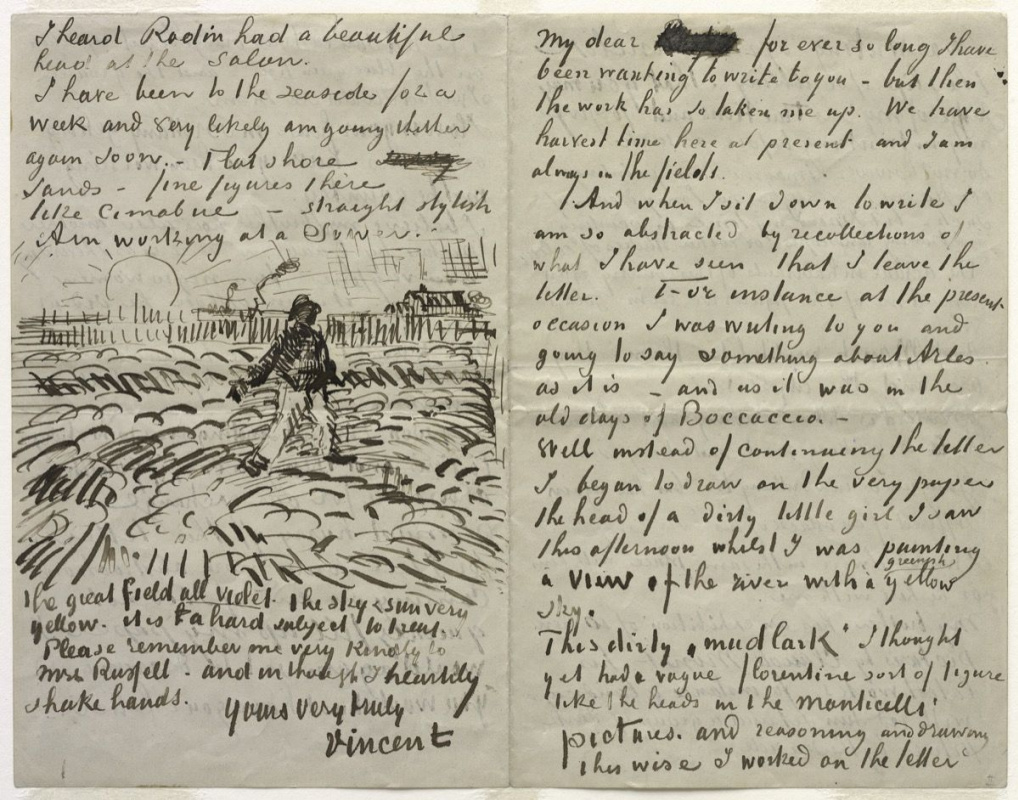

Van Gogh wrote a letter to his friend, Australian painter John Peter Russell, in mid-June of 1888, when he was 35. In slightly slanting, elegant script, he relates that he’s been meaning to write, but has been consumed by work; it’s harvest season in Arles, and he’s "always in the fields," which is reflected in the charming line drawing on the left side of the letter.

McKnight points to way the artist’s personal pronoun I indicates the isolation van Gogh felt. "There is an emotional disconnect and distance," she offers. Another notable clue is the word "present," which trails off into the far-right margin—a possible sign of depression, McKnight says.

Left: Vincent van Gogh. Self-portrait in a straw hat with a pipe, 1887.

Frida Kahlo

Throughout her tumultuous three-decade relationship with Diego Rivera that began in 1927—it included affairs among both parties, marriage, divorce, and remarriage—Kahlo kept a diary, in which she would write passionate letters to her beloved. Two of these letters, drawn from a 2005 book of the artist’s romantic correspondence with Rivera, are filled with dramatic odes ("I'd like to paint you, but there are no colors, because there are so many, in my confusion, the tangible form of my great love").

McKnight remarks on the legibility of the artist’s writing. "She does not rush through or write with haste; the writing is deliberate and methodical," she explains. The way that the Is are dotted, "with deliberate, definite pressure" she notes, shows "consistent attention to detail."

Left: Frida Kahlo. Self-portrait with monkey, 1945.

- Letter fromThe Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait. © Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

- Letter from The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait. © Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

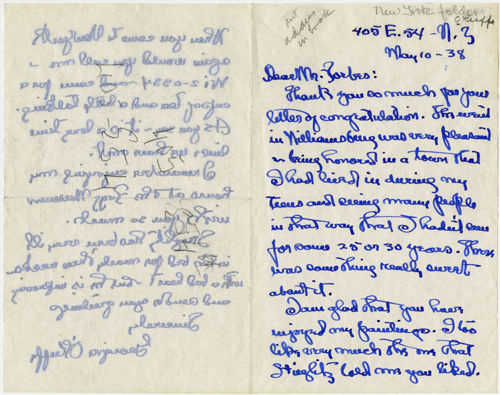

Georgia O’Keeffe

O’Keeffe wrote with an unusual trait that is "rarely seen in modern times," McKnight notes. "Notice the unusual parallel strokes in her letters D and T in the words ‘honored,' ‘lived,' ‘about,' and ‘sweet.'" McKnight refers to this stroke as the "master craftsman," and notes that it has been associated with "one who is a perfectionist in their work."

She also points to the artist’s "T-bars," or the way she crosses her Ts: long, thin lines that at times exceed the length of the word, (for example, in "town," and "that"). This, McKnight notes, can be revealing of "intermittent periods of extreme confidence and charisma."

Finally, McKnight points to the large "P buckles," the circles in the letter P—in "pleasant" and "people"—which could indicate that O’Keeffe possessed "a higher than average sex drive."

Left: Alfred Stieflitz, Photograph of Georgia O’Keeffe, seen nestled on a cushion on the ground, with her sketchpad and watercolors by her side, 1918. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Pablo Picasso

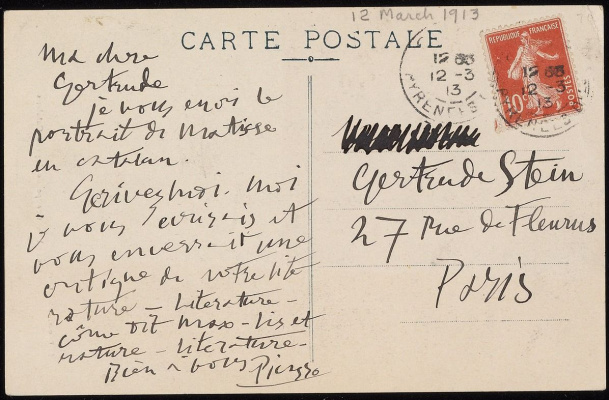

Picasso wrote to his friend in Paris, writer and art patron Gertrude Stein, in March of 1913. At the time, the artist was living in a French town in the Pyrenees with one of his lovers, Eva Gouel. On the postcard, he writes playfully, joking that the photograph on the front (depicting three Catalan men drinking), includes a "portrait of Matisse as a Catalan." He then asks Stein to write to him, and tells her he will write a review of her literature.

The brusque, hasty nature of the handwriting, McKnight says, suggests that Picasso "trusts himself to shoot from the hip" and "writes with haste." His writing lacks the purpose, conscientiousness, and "careful, deliberate strokes" that can be seen in the handwriting of Michelangelo. "He's in a hurry to get his thoughts down on paper, and his mind works very quickly," she explains, adding that the script also suggests Picasso was feeling optimistic at the time.

Like O’Keeffe, the artist crosses his Ts with long, sweeping lines, which, McKnight says "reveal definite charisma, confidence, and a lot of emotional energy." Additionally, the tent-like shape of his Ts may indicate stubbornness, while his Ms and Ns point to intelligence.

Left: Letter from Pablo Picasso to Gertrude Stein. © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

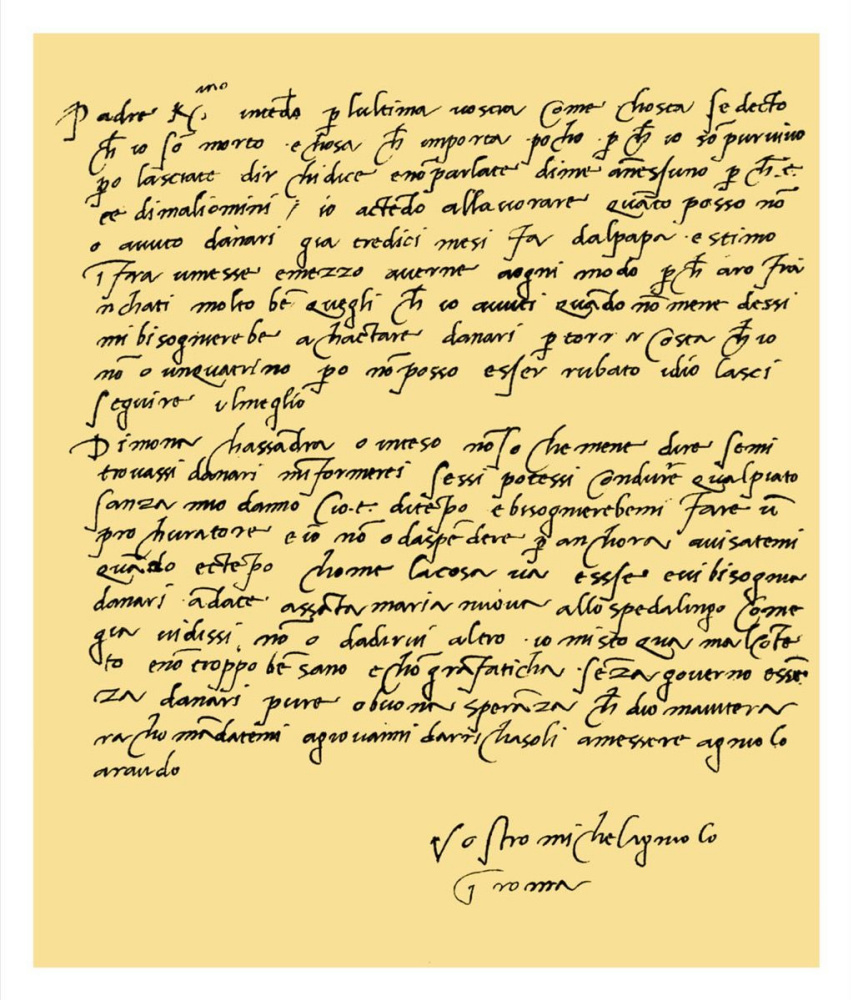

Michelangelo Buonarroti

McKnight remarks on the "artistic, almost musical" nature of Michelangelo’s handwriting, and points to the exacting and even baseline, which can be seen as a sign of stability. The many breaks within words, and between letters, can be a sign of extreme intuitiveness. Additionally, the small, intricate text nods to the artist’s powers of concentration.

"Many of the ending strokes to the last letters of words go up at a 45-degree angle, which specifically reveals a mindset of courage and a mindset of not seeing problems, only solutions," McKnight concludes.

Title illustration: Vincent van Gogh. Sketch from a letter of Pierre Bonnard. Van Gogh talks about working on Still Life with Coffee Pot, Pottery, and Fruits.