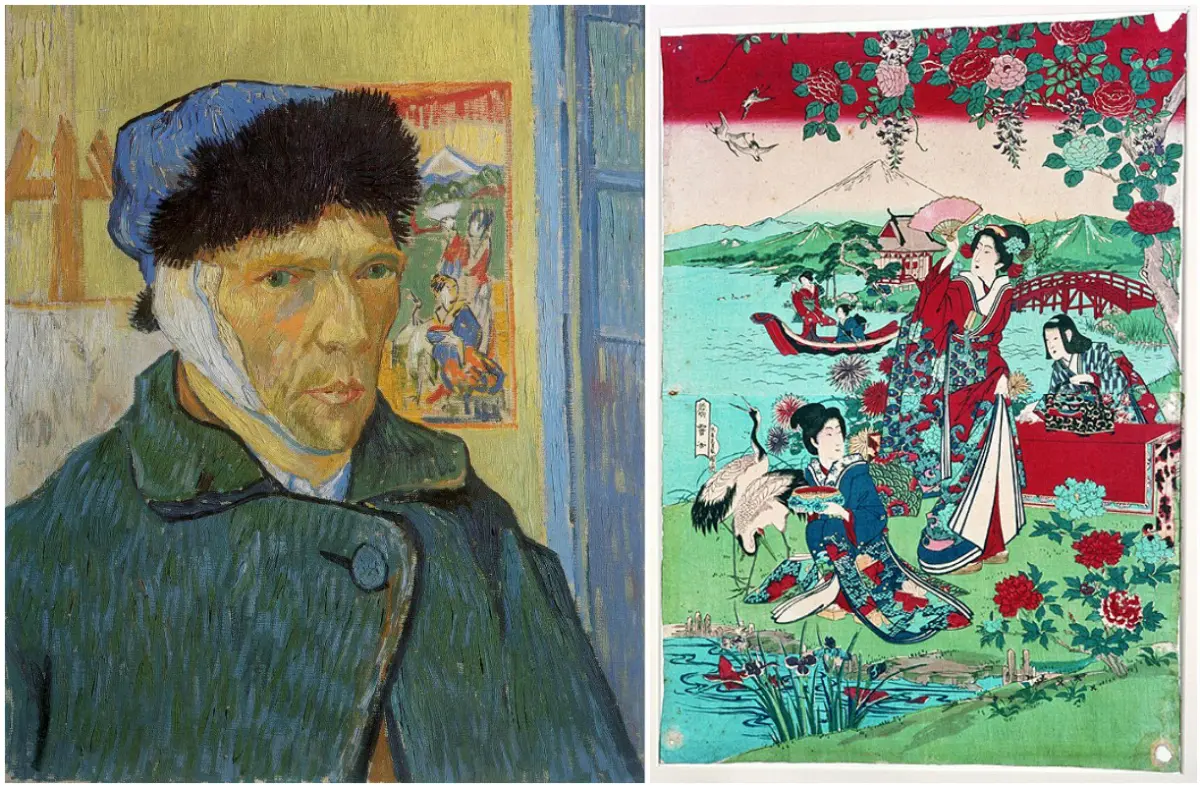

Vincent became one of the most avid lovers and collectors of ukiyo-e prints or Japanese pictures of the floating world, as well as of Japanese albums created for export. Having bought first stack of prints in Antwerp, van Gogh was fascinated by them studied them very carefully. A year later, when the artist moved into his brother’s apartment in Paris, he discovered that the German art dealer Siegfried Bing sold Japanese artworks and decorative objects at very reasonable prices in the Bing Gallery next to the place where Van Goghs dwelled. So, he and his brother immediately bought about 660 prints for just a few cents a piece.

Ms. Bakker, one of the exhibition’s four curators, said that van Gogh originally held an exhibition trying to resell the prints, but it wasn’t successful, and instead he hung onto them, tacked them to the walls of his studio and used them for inspiration. About 500 of them survive, and are now part of the Van Gogh Museum’s permanent collection.

At first, van Gogh just copied the works, making pencil sketches and oil paintings after Japanese masters (see two of them after Utagawa Hiroshige above). To make them look more exotic, he added sort of a border of arbitrary characters borrowed from other Japanese prints, because, of course, he did not know a word in Japanese. And even though he duplicated imagery of the prints, his every brush stroke added something of his own, regards Jonathan Jones, the art-critic of the Guardian.

In 1887, Van Gogh traced in pencil and ink the cover of an issue of the magazine Paris Illustré devoted to Japan and afterwards made a large-scale oil painting in the same fashion "Courtesan (After Eisen)," based on a piece by Japanese artist Kesai Eisen.

Similarly to the other copies he made, he gave this piece a border around the figure with motifs from other Japanese prints: the watery landscape with bamboo canes, water lilies, frogs, cranes and, in the distance, a little boat. Not accidentally did Vincent choose the animals for the frame: in 19th century France, prostitutes were often referred to as grues (cranes) or grenouilles (frogs); so, here we see depictions of animal metaphors referring to the woman’s profession.

Van Gogh copied and enlarged the figure by Kesai Eisen, tracing on a grid, giving her a colorful kimono and placing her against a bright yellow background. His colors are brighter and contrasts are more enhanced compared to the original piece.

Above: Vincent van Gogh, "Courtesan (After Eisen)," 1887. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Père Tanguy was rather important figure for Vincent van Gogh and other artists at the time. Julien-François Tanguy (1825−94) ran a small paint supplies shop in Montmartre and often took art works in exchange for the goods he sold. He was affectionately called "Père Tanguy" by artists and Van Gogh valued his friendship enormously.

At Tanguy’s shop the avant-garde met and artists could see sort of a latest art that was not accepted anywhere else. Here, Van Gogh could find paintings by Sezanne, Neo-Impressionists, and other Avant-garde artists.

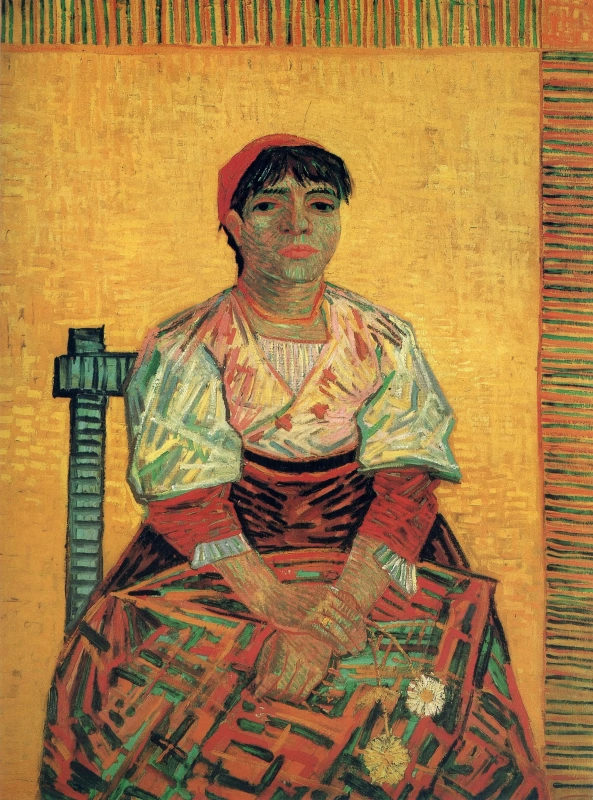

In this portrait, with which the shopkeeper never parted, the pure colours, the use of contrasting complementary colours, and the flat picture space are all inspired by Japanese art. Van Gogh chose to represent the old man in a strictly frontal pose, immobile, lost in thought, with his hands clasped over his stomach, turning him into a sort of Japanese sage, placed against a background filled with some of the countless brightly coloured Japanese prints that the painter and his brother Theo collected.

Above: Portrait of Père Tanguy, 1887. Musee Rodin, Paris

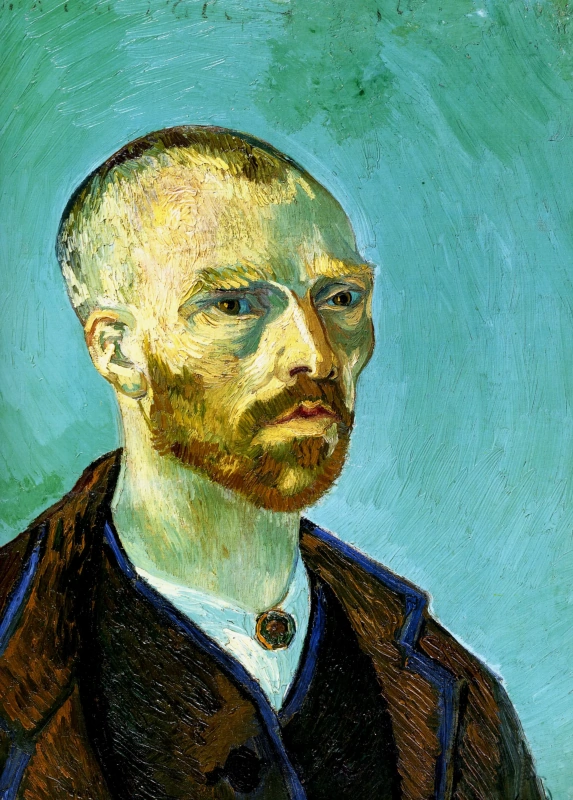

In this self-portrait the contrast between the graceful ideals Van Gogh saw in Japanese art and his own tortured reality is very painful. The man staring at us from behind blue eyes is far from the calm that the Japanese landscape on the print provides. "He is a harrowed modern saint, a Dostoyevskyan character on the edge of society and fighting to stay sane," says art critic Jonathan Jones about this art work.

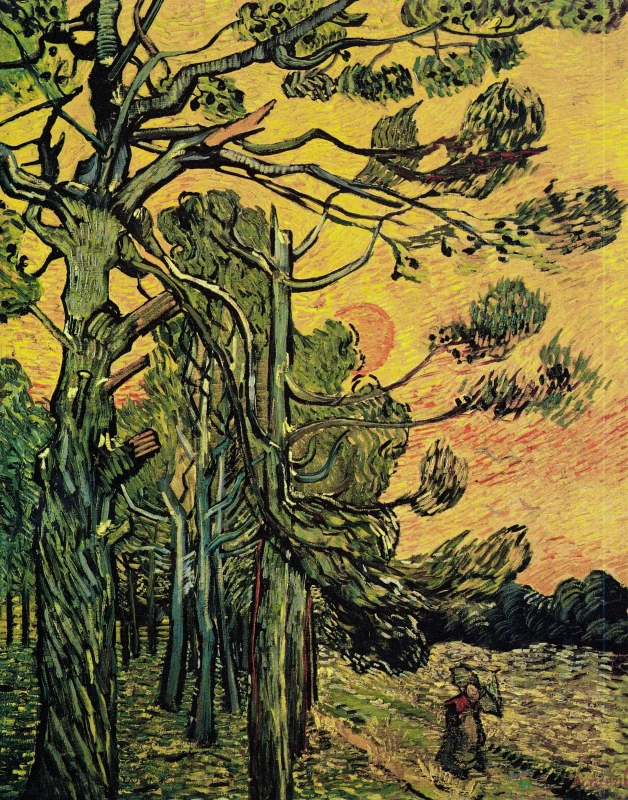

After spending two years in Montmartre, Vincent van Gogh has fled to Provence for a new inspiration, away from hectic Paris. He was longing for an ideal place where he could define himself as a modern painter and dreamed to organize an artistic commune there. In this context, Japan and its art became of utmost importance for him, more so even than it had been in Paris. In rather unusual way, Van Gogh equated Arles and Provençal landscape with Japan and its landscape . He never visited Japan, his knowledge of it was quite varied but he imagined it to be like Provence.

He continued in his letter to his friend Emile Bernard: "I want to begin by telling you that this part of the world seems to me as beautiful as Japan for the clearness of the atmosphere and the gay colour effects. The stretches of water make patches of a beautiful emerald and a rich blue in the landscapes, as we see it in the Japanese prints. Pale orange sunsets making the fields look blue — glorious yellow suns. However, so far I’ve hardly seen this part of the world in its usual summer splendor… The Japanese may not be making progress in their country, but there’s no doubt that their art is being carried on in France."

In a letter to his brother Theo from Provence he remarked: "Look, we love Japanese painting, we’ve experienced its influence — all the Impressionists have that in common — and we wouldn’t go to Japan, in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all."

A month later he wrote, "All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art…"

Vincent van Gogh used Japanese art model in response to the call for a modern, more primitive kind of painting. In the essay prepared for the exhibition "Van Gogh & Japan", the Van Gogh Museum states that "Japanese prints, with their expanses of colour and their stylisation, showed him the way, without requiring him to give up nature as his starting point. It was ideal."

Title illustration: Left: Hiroshige’s The Residence with Plum Trees at Kameido, 1857; right, Flowering Plum Orchard (after Hiroshige) by Vincent van Gogh, 1887. Composite: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).