"We often look at an image as if it was meant to be that way from the beginning," says co-author Marc Walton, a research professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern University. "But with these analytical images, we can get into the mind of the artist and better understand the creative process."

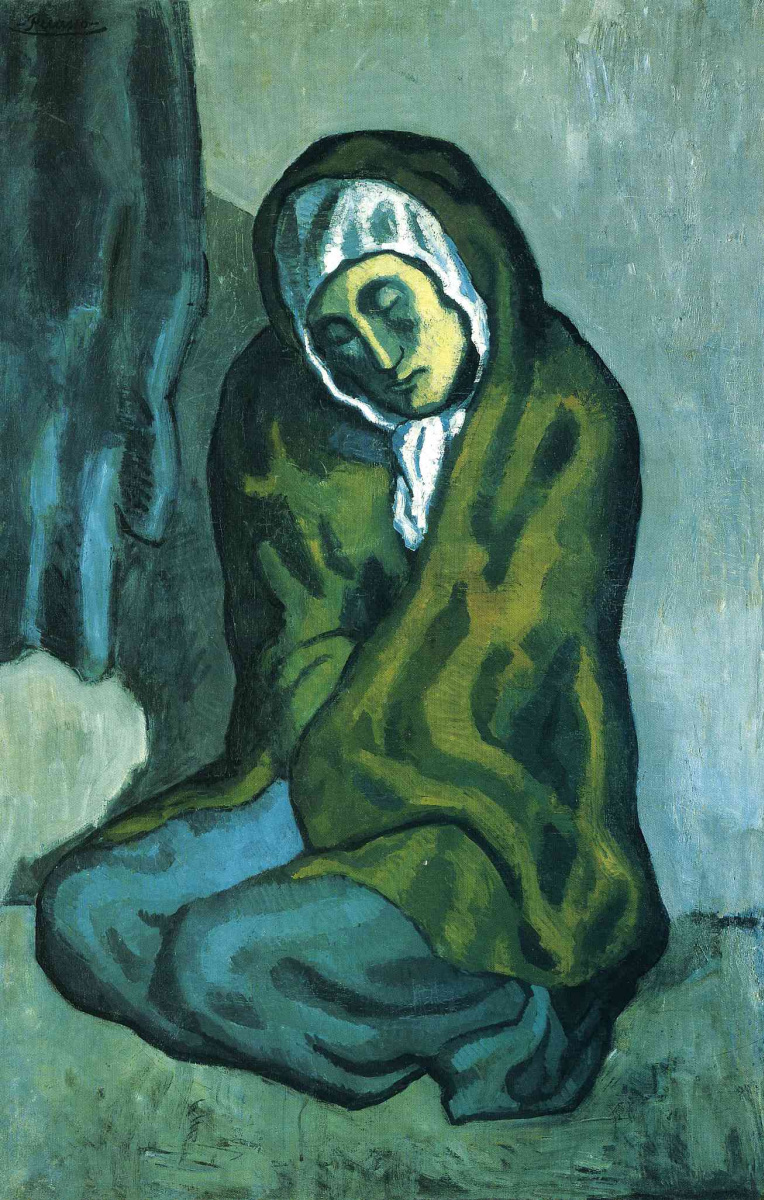

The painting was sold in 2015 at Christie’s auction in New York for $149,000 (£106,000). Now its owner is the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada (AGO).

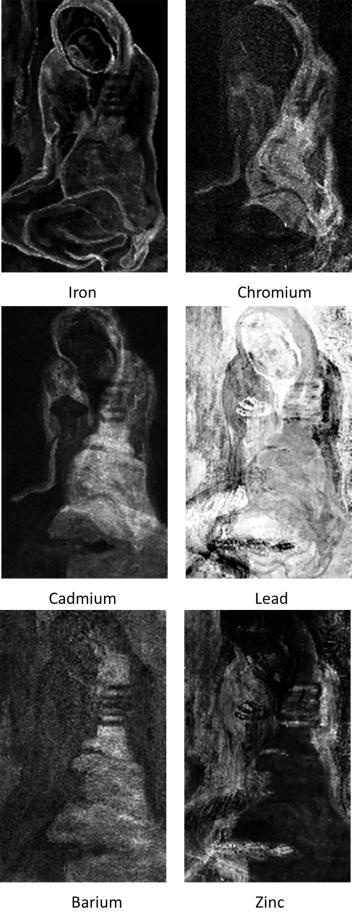

Curators first took X-ray images of this painting in 1992. Metals in the paint responded differently to X-rays, revealing a hidden landscape painted by another artist, who used different colors than Picasso. But the previous X-rays weren’t nearly as detailed as technologies today can provide. Also, a newer technique, called X-ray fluorescence scanning, or XRF, revealed new aspects of Picasso’s approach to painting that weren’t really possible to discern in the '90s.

Left: Sandra Webster-Cook (left) and Kenneth Brummel, both of the Art Gallery of Ontario, examine the portable x-ray fluorescence scanner.

By rotating the artist’s work 90 degrees, Picasso was able to use some of the landscape forms, such as the lines of the cliff edges into the woman’s back, in his own final composition.

It shows that the innovative modernist was inspired by the dominant lines of an underlying landscape painted by an unknown artist.

"He didn’t scrape the canvas or put a preparatory layer over it," Brummel says. "Picasso saw this landscape , found inspiration, and decided he was going to paint it, immediately."

"We think now it’s a landscape painted by someone enrolled at the fine arts academy in Barcelona, someone in Picasso’s orbit but not in his close circle," Brummel says.

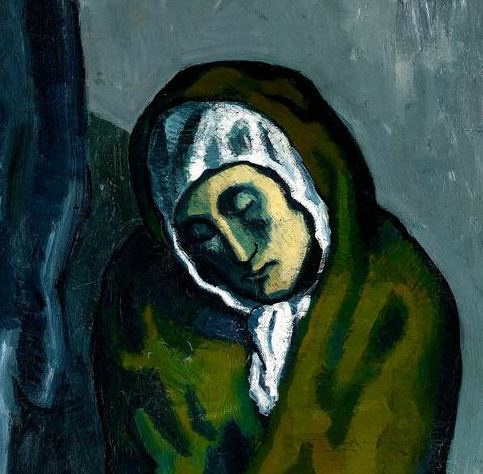

For the investigation, John Delaney from the National Gallery of Art performed a series of spectroscopy scans on "La Miséreuse accroupie." Delaney’s fiber-optic reflectance spectroscopy scans imaged the painting at various wavelengths, from the near-infrared to the infrared. These revealed the precise pigments Picasso had used.

While the distribution of iron and chromium pigments matched well with the figure of the woman as seen today, the spread of cadmium and lead based pigments provided insights into the puzzling surface features.

The distribution of these pigments showed slight differences in the tilt of the woman’s head and revealed that the artist had initially painted the woman with her right arm and hand, possibly holding a piece of bread, before covering it with her cloak in the final version. The researchers also found in the earlier versions, the woman was narrower and had a different head inclination.

Left: Chemical mapping of the pigment layers in "La Miséreuse accroupie" revealed multiple iterations of the woman’s hand position.

that x-ray technology could one day

discover a lost work underneath one of his early paintings.

"The portability of the instrumentation is a gift," says Sandra Webster-Cook, senior conservator of paintings at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Previously artworks had to be transported for scanning to facilities that can afford and accommodate large commercial scanners. This effort was one of the first times when tools came to art, rather than the other way around.

Webster-Cook says her museum is currently conducting a similar analysis on another of Picasso’s Blue Period works, "La Soupe." And for his part, Walton is interested in seeing the results of analysis of a Gauguin painting at the Harvard Art Museum, which has curious surface textures that don’t match the visible image.

Left: Pablo Picasso. La Soupe, 1902.

Based on materials The Guardian, BBC, National Geographic.