The term «neorealism» in the history of contemporary art arose to unite several art movements that appeared and developed throughout the 20th century, and there is something to be said about each of them. For the first time, they spoke of neorealism in 1914 in Great Britain. The next trend to receive this name, was Italian neorealism (1946-1955), which influenced cinema and fine art. Finally, a practically similar name New Realism (Nouveau Réalisme) was given to an innovative movement that arose in France in the 1960s. Let us examine each of these movements in detail and find out how much “new” was the concept of realism at different periods of the contemporary European art.

English neo-realism during the First World War

Artists Charles Ginner and Harold Gilman were apparently the first to introduce the term “neo-realism” into the vocabulary of art. Both painters were members of the London Camden Town Group (1911—1913), which brought together post-impressionists influenced by the creative research of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. The artists frequently gathered at Walter Sickert’s studio in the London Camden area. The Camden Town group included 16 artists, including Camille Pissarro's eldest son - Lucien, the future director of the London Tate James Manson, an art theorist Percy Wyndham Lewis, and set designer Spencer Gore. The main heritage of this art group is paintings depicting the views of everyday London and the characteristic social types of representatives of various classes that arose in the pre-war period, as well as during the First World War.

Harold Gilman. "Mrs. Mount at Her Breakfast", 1917

Walter Sickert. Harold Gilman. 1912. Source

Harold Gilman and his friend Charles Ginner have always been in the thick of European modernist artistic movements. Ginner was born and raised in France and got his standing in everything related to the latest European trends in painting for his British colleagues. The "Мanet and Post Impressionists" exhibition at Grafton Galleries (1910) had a huge impact on London artists, prompting them to the next search for new meanings and methods of their artistic expression. After a joint trip to Paris, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Мatisse have become Gilman’s idols, as well as Ginner’s.

Harold Gilman and his friend Charles Ginner have always been in the thick of European modernist artistic movements. Ginner was born and raised in France and got his standing in everything related to the latest European trends in painting for his British colleagues. The "Мanet and Post Impressionists" exhibition at Grafton Galleries (1910) had a huge impact on London artists, prompting them to the next search for new meanings and methods of their artistic expression. After a joint trip to Paris, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Мatisse have become Gilman’s idols, as well as Ginner’s.

1.1. Harold Gilman. Mary L. Harold Gilman (Profile Portrait). 1914

1.2. Harold Gilman. Mother and Child. 1918

On the eve of the First World War, Gilman and Ginner felt the need to explore modernity and everyday life through new forms and colours. Their works had characteristic short, vibrant brush strokes and bright colours. Charles Ginner described his intentions and new views on contemporary British art in his manifesto Neorealism published on 1 January 1914 by New Age publishers.

1.2. Harold Gilman. Mother and Child. 1918

On the eve of the First World War, Gilman and Ginner felt the need to explore modernity and everyday life through new forms and colours. Their works had characteristic short, vibrant brush strokes and bright colours. Charles Ginner described his intentions and new views on contemporary British art in his manifesto Neorealism published on 1 January 1914 by New Age publishers.

Charles Jeanne. The Fruit Stall, King’s Cross. 1914

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund © Estate of Charles Ginner

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund © Estate of Charles Ginner

As follows from the manifesto, “... all the great artists, directly communicating with Nature, drew previously unseen facts from it and interpreted them through their own expressive methods – this was a great tradition of realism...” But Ginner felt that some of his contemporaries created works that simply mimicked the innovations of the great realists Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin and Van Gogh: “...academicist artists just ... adopt these manners, that’s all they can see in the works by these artists, they make formulae out of them”. The neo-realism of Gilman and Ginner challenged formal art: “...This new academicism, which will ultimately destroy art ... we must contrast with the young and healthy realistic movement, the new realism, that is, ‘neorealism’”.

Charles Ginner. The Circus. 1913

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) © Estate of Charles Ginner

The Neorealism manifesto became a kind of preface to the exhibition of both artists in the Goupil Gallery, which opened in April of the same year. Another artist, Robert Bevan joined Gilman and Ginner in their views and principles of neorealism. Gilman presented his views to students at the Westminster School of Art, and then at his own school, which he founded with Ginner. In 1916, Ginner joined the army as a military artist. After the war, he continued his close collaboration with Gilman, sharing a studio on Maple Street with him. Together with Frank Rutter, the founder of the Allied Artists Assotiation (AAA), the English likeness of the Paris Independent Salon, in 1917, they created Art and Letters. It was a modernist quarterly illustrated magazine, conceived by artists before the war, which brought together literature, art and politics.

Robert Bevan. The Weigh House, Cumberland Market. 1914

In 1919, Ginner, followed by Gilman, fell ill with the Spanish flu, an extremely dangerous type of flu, which affected nearly 30% of the world’s population in 1918–1919. In both, the flu soon grew into pneumonia, which caused the death of Gilman, who was very painful since his childhood. As Ginner wrote later, it was “...a big loss for [British] contemporary art movements...”, “which owe much to Gilman’s efforts, ... whose achievements in painting and whose keen interest in all attempts to unite artists will remain in history”.

Italian neorealism and the “New Front of the Arts” group

The next country to host the neorealist movement was Italy. This was most clearly expressed in post-war cinema, as well as in painting.

Poster for the film "Rome, Open City" Source

Neorealism in cinema reflected the economic and moral hardships of post-war Italy, the poverty and despair of ordinary people. The new style was developed among filmmakers, which revolved around the Cinema magazine; this included Luchino Visconti, Gianni Puccini, Cesare Zavattini and others. Neorealism became known throughout the world in 1946 thanks to Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City film, which received the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. However, the first film in the new style is considered the debut directorial work by Luchino Visconti Ossessione (“Obsession”), (1943).

Neorealism in cinema reflected the economic and moral hardships of post-war Italy, the poverty and despair of ordinary people. The new style was developed among filmmakers, which revolved around the Cinema magazine; this included Luchino Visconti, Gianni Puccini, Cesare Zavattini and others. Neorealism became known throughout the world in 1946 thanks to Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City film, which received the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. However, the first film in the new style is considered the debut directorial work by Luchino Visconti Ossessione (“Obsession”), (1943).

A shot from the Obsession film by Luchino Visconti, 1943. Source.

Neorealism in Italian cinema is primarily characterized by a general atmosphere of authenticity, naturalness. American film expert Peter Bondanella defined the following principles inherent in this style:

- a specific social context;

- a sense of historical relevance and immediacy;

- political commitment to progressive social change;

- real field shooting as opposed to studio shooting;

- rejection of classic Hollywood acting clichés;

- the widest possible use of non-professional actors,

- documentary style.

According to the famous Poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, the Russian movement of the Sixtiers arose precisely because of this cultural trend: “there is no small suffering, no small people – that’s what Italian neorealism taught us again.”

Emilio Vedova. The Impact. 1949

In Italian painting, the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti (“New Front of the Arts”) was at the origins of the new movement. It was an association of anti-fascist artists of various genres who proclaimed their goal to create new artistic values. In 1946, the Manifesto of Realism was signed by artists and sculptors, whose cultural standard was Picasso’s Guernica. The neo-Cubist style became decisive for the association, one of the main ideologists of which was the Sicilian artist Renato Guttuso. The artists advocated “the classic of the modern figurative tradition, which begins with Cézanne and develops in Fauvism and mainly in Cubism”. The artist such as Antonio Corpora, Giuseppe Santomazo, Emilio Vedova, Ennio Morlotti joined the New Front of the Arts.

Распятие

1941, 198.5×198.5 см

The main themes of the Italian neorealists’ artworks were the life of the post-war country, the struggle of ordinary people for their rights. Artists advocated humanism and equality, the value of simple moments of everyday life, sang the heroism of their people, who desperately resisted fascism during the war years. Their works were characterized by a dynamic composition, expression, saturated colours. The ideas of the New Front of the Arts were reflected in the works by artists from other countries – the Mexican Diego Rivera, the German Fritz Kremer, the Frenchman André Fougeron.

Продавщица цветов

1949

In the following years, disputes between abstractionist artists, who were the supporters of the art free from the need to describe reality, and realists artists, who manifested the artistic expression of tension and contradictions within the society. In 1950, the association broke up because of its internal disputes.

New Realism of the early 1960s in France

In the early 1960s, a group of artists formed in France, whose intent was to prove the death of art and find the new meanings in material reality. They called themselves the Nouveau Réalisme group, or New Realism – the “new realists” became the third component in the progressive French cultural movements Nouveau Roman (literature) and New Wave (cinema). The New Realists questioned the idea that art should politicize or idealize any subject.

Карта Марса водой и огнем

1961, 69×49 см

The Nouveau Réalism group was founded in 1960 by art historian Pierre Restany and artist Yves Klein during the first collective exhibition at the Apollinaire Gallery in Milan. Pierre Restany wrote an original manifesto for the group entitled “Constituent Declaration of New Realism”, proclaiming that “Nouveau Réalisme is the new ways of perceiving reality”. This joint declaration was signed on 27 October 1960 in the studio of Yves Klein by nine artists, including Armand, Martial Raysse, Pierre Restany, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tangley, François Dufrene, Raymond Hains, and Jacques de la Villeglé. A year later, Cesar Baldaccini, Mimmo Rotella, Niki de Saint Phalle and Gérard Deschamps joined them. The actionist artist Christo Javacheff also supported the interests of the association.

Пит-стоп

1984, 360×600×600 см

Following the Dadaists, the “new realists” operated on ready-made objects, making them part of art objects or presenting them in their usual form without embellishment: the garbage heap became an installation, a smashed car – a sculpture, a spot of paint on the wall – a picture. Destruction was a way of creation; parts of objects became parts of new exhibits. Artists used cars, fire, and even weapons to interact with objects and materials in a new way.

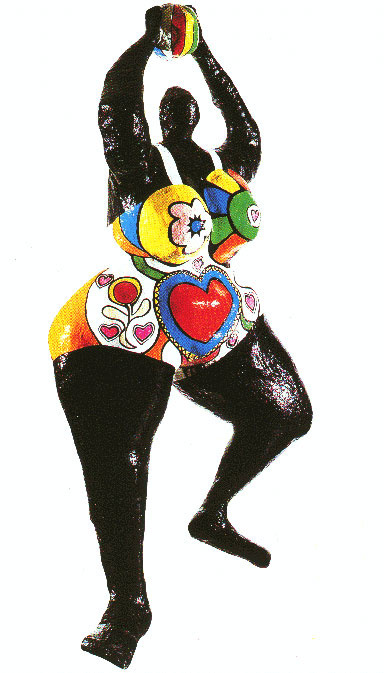

Черная Венера

XX век

The movement sought to destroy the image of the artist as a lonely person working in the studio, creating valuable works of art for privileged galleries or museum spaces. For the members of the association, it became commonplace to collaborate in projects and create or display their work in public places. Often the audience was invited to participate in the creation of works of art, which stimulated a new level of entertainment and the viewer involvement. These actions were concerned institutional criticism and the liberation of the spirit of creativity.

Посвящение Нью-Йорку (фрагмент)

1960, 203.7×75×223.2 см

Despite the fact that the New Realism movement only existed until 1970, its influence is still widespread – perhaps because it offered countless opportunities for self-expression for each artist.

Title illustration: Charles Ginner. Piccadilly Circus. 1912

Title illustration: Charles Ginner. Piccadilly Circus. 1912