Storms, eruptions, hurricanes, and tornadoes brought big moments to many artists. We picked ten canvases to prove this to you.

While the survivors are licking their wounds and count losses from devastation made by Hurricane Irma in the South and North Americas, the others are looking through pictures and videos taken from the eye of the storm. Well, it’s in our human nature to fix the horrors of catastrophes and to examine them thoroughly.

Now it’s hard to imagine that once there were no cameras to take pictures or make videos, and artists were those who, mesmerized by the eruptions, storms, hurricanes, and tornadoes, captured them on canvases with vibrant detail. To many their pictures brought moments of fame.

Now it’s hard to imagine that once there were no cameras to take pictures or make videos, and artists were those who, mesmerized by the eruptions, storms, hurricanes, and tornadoes, captured them on canvases with vibrant detail. To many their pictures brought moments of fame.

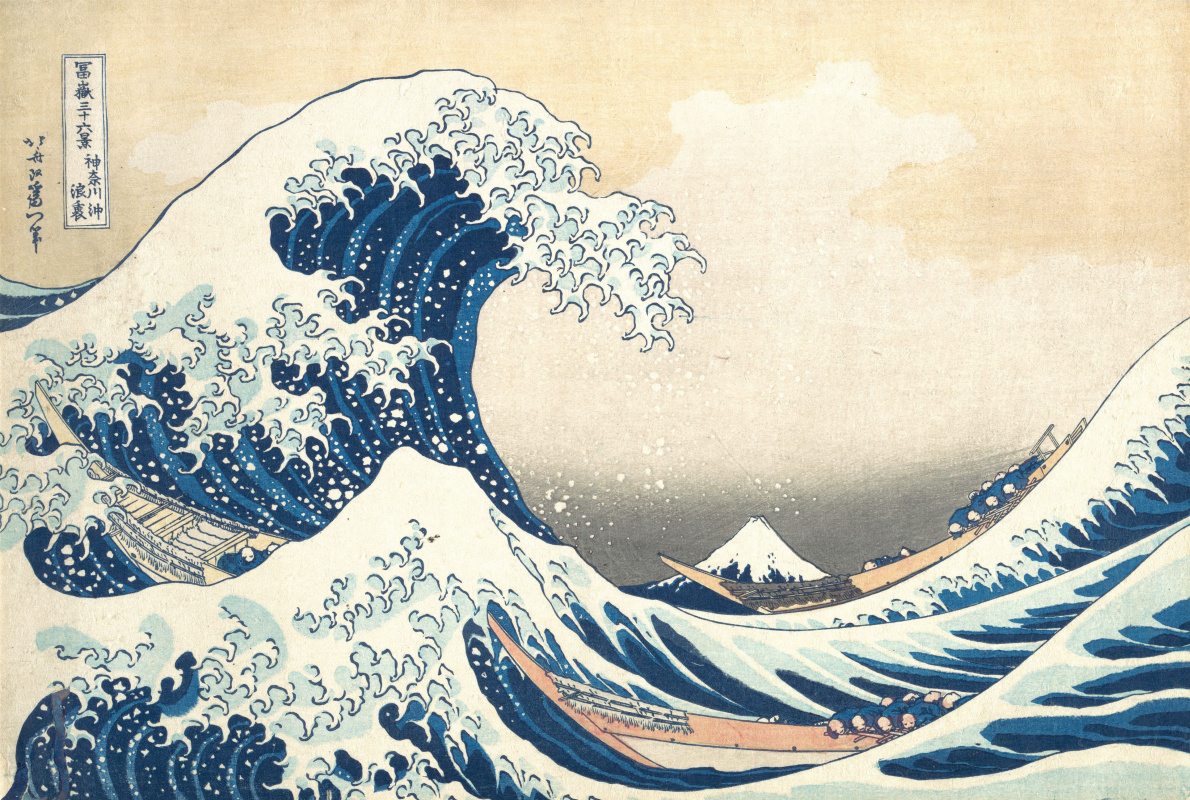

1. The Great Wave by Katsushika Hokusai, ca. 1830-32

The great wave off Kanagawa

1832, 25.7×37.9 cm

The Great Wave, also known as Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), is the best-known work by Japanese artist Hokusai Katsushika (1760−1849). It is the first woodblock print from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei) that made him famous all around the world.

Its prints began to circulate widely through Europe and inspired many artists, including the Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh, the French Impressionist composer Claude Debussy, who created his symphonic masterpiece La Mer (The Sea) and even put the print on its first edition, and the Austro-German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who wrote a poem "Der Berg" ("The Mountain").

Copies of the print were bought by several Western institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the British Museum in London, the Art Institute of Chicago and the National Library of France.

Now the interesting thing is that this great wave is no tsunami, although the great might of the wave is about to strike the boats as if it were an enormous monster. It is so huge that it makes the mountain look minute and the boats seem doomed for shipwreck. Such destructive violence had made many to think The Great Wave is a tsunami. However, scholars have done a thorough research and determined that it’s a rouge wave, or "a plunging breaker" in scientists' language.

Its prints began to circulate widely through Europe and inspired many artists, including the Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh, the French Impressionist composer Claude Debussy, who created his symphonic masterpiece La Mer (The Sea) and even put the print on its first edition, and the Austro-German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who wrote a poem "Der Berg" ("The Mountain").

Copies of the print were bought by several Western institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the British Museum in London, the Art Institute of Chicago and the National Library of France.

Now the interesting thing is that this great wave is no tsunami, although the great might of the wave is about to strike the boats as if it were an enormous monster. It is so huge that it makes the mountain look minute and the boats seem doomed for shipwreck. Such destructive violence had made many to think The Great Wave is a tsunami. However, scholars have done a thorough research and determined that it’s a rouge wave, or "a plunging breaker" in scientists' language.

2. The Ninth Wave by Ivan Aivazovsky, 1850

The ninth wave

1850, 221×332 cm

The Ninth Wave was created by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817−1900), a Russian painter who is considered one of the greatest marine

artists in art history. This enormous canvas is one of his best-known works. Its title refers to a colloquial expression among Russian seafarers actually meaning 'a rouge wave', the same as on the Japanese print.

We see that moment when tiny sailors, enduring a shipwreck, are clinging to their makeshift vessel made from a surviving mast. However, the wave threatens to engulf them at any moment. There’s a sad irony in the picture: Aivazovsky uses warm sunny colors that make the air and the sea glisten, yet it is still a storm, and the seascape is foreboding. We hope that people will be saved yet we know that they are in dire straits.

Aivazovsky was born in Feodosia, an ancient city on the Black Sea shore. He loved the sea and has studied its changing moods. He had a rare gift of paining from memory. He never painted the sea from real life, only made studies on the shore. That’s why his absolutely realistic seascapes had enormous sizes and were done in short terms.

We see that moment when tiny sailors, enduring a shipwreck, are clinging to their makeshift vessel made from a surviving mast. However, the wave threatens to engulf them at any moment. There’s a sad irony in the picture: Aivazovsky uses warm sunny colors that make the air and the sea glisten, yet it is still a storm, and the seascape is foreboding. We hope that people will be saved yet we know that they are in dire straits.

Aivazovsky was born in Feodosia, an ancient city on the Black Sea shore. He loved the sea and has studied its changing moods. He had a rare gift of paining from memory. He never painted the sea from real life, only made studies on the shore. That’s why his absolutely realistic seascapes had enormous sizes and were done in short terms.

Watch how the sea changes its mood in animated paintings by Aivazovsky:

3. The Act of Sacrifice Made by Captain Desse towards the Dutch Ship Columbus by Jean Antoine Theodore Gudin, 1829

The painting above is the work of the 19th century French marine

artist and a sailor Baron Jean Antoine Theodore Gudin (1802−1880). A sensation caused by his maritime landscapes during his first exhibition at the Salon in 1822 transformed into his artistic triumph when he exhibited this work at the Salon in 1831. It was commissioned to Gudin by the Ministry of Interior to praise the French Navy; it costed 6,000 francs.

Its subject is based on a real story of a shipwreck that occurred during a heavy storm on July 13th, 1822 near Aiguilles banks. On that day, the brig La Julia, under the command of Captain Desse, met on her way the Dutch ship Colombus, dispatched from Batavia to Amsterdam. The ship had almost a hundred men, women, and children on board and was almost completely destroyed by the violent storm. The furious water and wind had taken away her main mast, a mizzen, a bowsprit, and has broken her rudders and bowthrustyrs.

Thus distraught, half open, she has been rolling in the midst of a merciless sea, and the crew waited for death only, when a sail came up on the horizon, moving towards Colombus. It was the French brig La Julia that has given people hope. Despite the danger that was at its height, for the mountains of water swept between the brig and the ship and threatened to engulf victims and saviors at any moment, Captain Desse shouted generously, "I will not abandon you!" He was repeating this cry louder and louder when the danger increased.

It took five extremely exhausting days between fear and hope to save ninety-two persons destined to perish. But Pierre Desse, Captain of La Julia, has kept his promise.

Ironically, in a year he was found liable for the loss of the Columbus' goods he had thrown into the sea to save people and had to pay a total sum of 87,550.37 francs. Even 20,000 francs obtained from the generous King of Holland did not help him and he was obliged, in order to discharge his debt, to sell La Julia.

Its subject is based on a real story of a shipwreck that occurred during a heavy storm on July 13th, 1822 near Aiguilles banks. On that day, the brig La Julia, under the command of Captain Desse, met on her way the Dutch ship Colombus, dispatched from Batavia to Amsterdam. The ship had almost a hundred men, women, and children on board and was almost completely destroyed by the violent storm. The furious water and wind had taken away her main mast, a mizzen, a bowsprit, and has broken her rudders and bowthrustyrs.

Thus distraught, half open, she has been rolling in the midst of a merciless sea, and the crew waited for death only, when a sail came up on the horizon, moving towards Colombus. It was the French brig La Julia that has given people hope. Despite the danger that was at its height, for the mountains of water swept between the brig and the ship and threatened to engulf victims and saviors at any moment, Captain Desse shouted generously, "I will not abandon you!" He was repeating this cry louder and louder when the danger increased.

It took five extremely exhausting days between fear and hope to save ninety-two persons destined to perish. But Pierre Desse, Captain of La Julia, has kept his promise.

Ironically, in a year he was found liable for the loss of the Columbus' goods he had thrown into the sea to save people and had to pay a total sum of 87,550.37 francs. Even 20,000 francs obtained from the generous King of Holland did not help him and he was obliged, in order to discharge his debt, to sell La Julia.

4. After the Hurricane, Bahamas by Winslow Homer, 1899

After the hurricane, Bahamas

1899, 38×54.3 cm

Winslow Homer (1836−1910) was an artist-correspondent for the Harper’s Weekly, a landscape painter and a printmaker, best known for his marine

subjects. He is regarded by many as the greatest American painter of the nineteenth century.

In the mid 1880s, Homer started visiting the Caribbean, then moved to Prout’s Neck, Maine, a peninsula ten miles south of Portland. He examined blue seas under blue skies of Florida, Cuba, and the Bahamas, the very same places being visited by Hurricane Irma this week.

After the Hurricane, Bahamas is one of the most famous Homer’s late watercolor seascapes. It was made after the Atlantic 1899 hurricane season which featured the longest-lasting tropical cyclone in the Atlantic basin. There were nine tropical storms, of which five became hurricanes. The most significant storm of the season was Hurricane Three, nicknamed the San Ciriaco hurricane which alone caused about $20 million (1899 USD) in damage and at least 3,656 deaths.

In the Bahamas, strong winds and waves sank 50 small crafts. Severe damage was reported in the capital city of Nassau, with over 100 buildings destroyed and many damaged. The death toll in the Bahamas was at least 125.

Homer’s watercolor fills us with sorrow for the lost struggle of people against the sea and with an understanding how fragile and transient our human life is, compared to the timelessness of nature.

In the mid 1880s, Homer started visiting the Caribbean, then moved to Prout’s Neck, Maine, a peninsula ten miles south of Portland. He examined blue seas under blue skies of Florida, Cuba, and the Bahamas, the very same places being visited by Hurricane Irma this week.

After the Hurricane, Bahamas is one of the most famous Homer’s late watercolor seascapes. It was made after the Atlantic 1899 hurricane season which featured the longest-lasting tropical cyclone in the Atlantic basin. There were nine tropical storms, of which five became hurricanes. The most significant storm of the season was Hurricane Three, nicknamed the San Ciriaco hurricane which alone caused about $20 million (1899 USD) in damage and at least 3,656 deaths.

In the Bahamas, strong winds and waves sank 50 small crafts. Severe damage was reported in the capital city of Nassau, with over 100 buildings destroyed and many damaged. The death toll in the Bahamas was at least 125.

Homer’s watercolor fills us with sorrow for the lost struggle of people against the sea and with an understanding how fragile and transient our human life is, compared to the timelessness of nature.

5. Vesuvius in Eruption by Joseph Wright of Derby, c.1776–80

Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples

1776, 122×176.4 cm

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734−1797) is a renowned English painter that has almost never left his home town except for several short tours to London and one travel to Italy in between 1773 and 1775. He was so impressed by what he had seen there that he drew on the experience for the rest of his career. He was mesmerized by the power of Mount Vesuvius, dominating the Bay of Naples and the surrounding area. He stayed in Naples for one months in 1774, so he just could not witness the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 1779. Yet he is best known for his dramatic scenes lit by the glare of an erupting volcano, for he has painted over thirty of them.

Researchers think that this picture was painted soon after Wright’s return to England, with the aid of the studies made on the spot. From the foothills of Vesuvius opens a dramatic scene defining the catastrophe in AD79. We see the red hot burning lava erupting from the Vesuvius crater and outbursting black ashes that form the dense black clouds gradually transforming into smoke streams floating across the bay above the absolutely tranquil sea. Wright deliberately included in his landscape two islands that wouldn’t be visible in reality to emphasize the striking contrast between hot and cold colors and between tranquility of the sea and violence of the volcano.

It’s hard to see clearly but there are four figures in the dark foreground, two men followed by two morning females. Men carry a dead body of one of the thousands killed by the volcano. Compared to the might of the great Vesuvius the human elements are insignificant in here. Wright stresses how small and unimportant they are before the sublime grandeur of nature.

Researchers think that this picture was painted soon after Wright’s return to England, with the aid of the studies made on the spot. From the foothills of Vesuvius opens a dramatic scene defining the catastrophe in AD79. We see the red hot burning lava erupting from the Vesuvius crater and outbursting black ashes that form the dense black clouds gradually transforming into smoke streams floating across the bay above the absolutely tranquil sea. Wright deliberately included in his landscape two islands that wouldn’t be visible in reality to emphasize the striking contrast between hot and cold colors and between tranquility of the sea and violence of the volcano.

It’s hard to see clearly but there are four figures in the dark foreground, two men followed by two morning females. Men carry a dead body of one of the thousands killed by the volcano. Compared to the might of the great Vesuvius the human elements are insignificant in here. Wright stresses how small and unimportant they are before the sublime grandeur of nature.

6. The last day of Pompeii by Karl Bryullov, 1830s.

The last day of Pompeii

1830-th

, 465.5×651 cm

The Last Day of Pompeii by the renowned Russian painter, portraitist and genre artist Karl Bryullov (1799−1852) shows us the same disaster but from the other point of view. We see the most catastrophic eruption in European history as doomed inhabitants of the Pompeii city, which was completely obliterated and buried underneath massive pyroclastic surges and ashfall deposits.

As a very talented student of St. Petersburg Academy of Arts on a fellowship, Bryullov spent many years in Italy. He was very interested in excavations made in Pompeii and Herculaneum at that time and spent many days in Pompeii doing his studies on the spot. Eventually, The Last Day of Pompeii, was warmly accepted by the public in Europe and in Russia, making him overnight one of the best known painters of his time.

This grandiose historical painting includes Bryullov’s own self-portrait. He immortalized himself in the image of an artist fleeing eruption with his most precious belongings, brushes and paints, in a box on his head. He’s on the left, in a group of people rushing out of a building. Now as many researches have been made, we know that nobody had a chance to stay alive. Those who failed to evacuate immediately as the smoke appeared from the Vesuvius, were burnt by very high temperature (300 C) and buried underneath massive substances released by the volcano.

As a very talented student of St. Petersburg Academy of Arts on a fellowship, Bryullov spent many years in Italy. He was very interested in excavations made in Pompeii and Herculaneum at that time and spent many days in Pompeii doing his studies on the spot. Eventually, The Last Day of Pompeii, was warmly accepted by the public in Europe and in Russia, making him overnight one of the best known painters of his time.

This grandiose historical painting includes Bryullov’s own self-portrait. He immortalized himself in the image of an artist fleeing eruption with his most precious belongings, brushes and paints, in a box on his head. He’s on the left, in a group of people rushing out of a building. Now as many researches have been made, we know that nobody had a chance to stay alive. Those who failed to evacuate immediately as the smoke appeared from the Vesuvius, were burnt by very high temperature (300 C) and buried underneath massive substances released by the volcano.

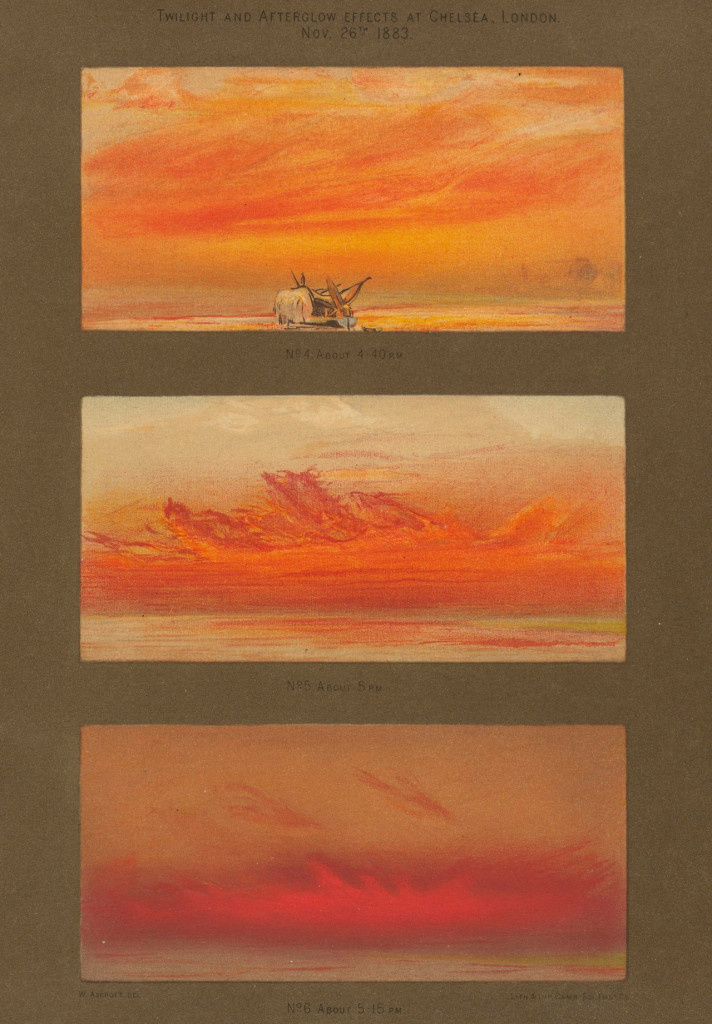

7. Pastel sunset sketches by William Ascroft, 1883-84

The greatest explosion of the volcano in modern times occurred on the tiny Indonesian island of Krakatoa (located halfway between Java and Sumatra) in August 1883. The eruption was so violent that it has changed the geography of the archipelagos dramatically. A series of tsunamis, thrown out by the force of the explosion, wiped out dozens of coastal villages, killing thousands of inhabitants. The disaster has taken away almost 40,000 people’s lifes.

The effects of the eruption were global. The volcano jettisoned billions of tonnes of ash and debris deep into the earths upper atmosphere so that the world temperatures dropped by 1.2 degrees C. Ash and sulphur dioxide gas were drifting down across the world and reacted with water vapor. By October/November 1883, people in different countries were experiencing amazing multi-coloured evening displays, caused by the scattering of light by the atmospheric particles. The spectacular sunsets caused public sensations world-wide. Naturally, painters were also attracted.

William Ascroft was hired by the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society (Great Britain) to make pastel sky-sketches depicting "afterglow of the eruption" from the banks of the Thames at Chelsea. Each evening starting fall 1883, the painter stumbled through country fields and lanes, frantically scratching on paper to catch the alluring visual oddities before they disappeared. He recorded more than 500 highly-colored sunsets which now form a prolific scientific report to remind us of the immense power of Earth.

The effects of the eruption were global. The volcano jettisoned billions of tonnes of ash and debris deep into the earths upper atmosphere so that the world temperatures dropped by 1.2 degrees C. Ash and sulphur dioxide gas were drifting down across the world and reacted with water vapor. By October/November 1883, people in different countries were experiencing amazing multi-coloured evening displays, caused by the scattering of light by the atmospheric particles. The spectacular sunsets caused public sensations world-wide. Naturally, painters were also attracted.

William Ascroft was hired by the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society (Great Britain) to make pastel sky-sketches depicting "afterglow of the eruption" from the banks of the Thames at Chelsea. Each evening starting fall 1883, the painter stumbled through country fields and lanes, frantically scratching on paper to catch the alluring visual oddities before they disappeared. He recorded more than 500 highly-colored sunsets which now form a prolific scientific report to remind us of the immense power of Earth.

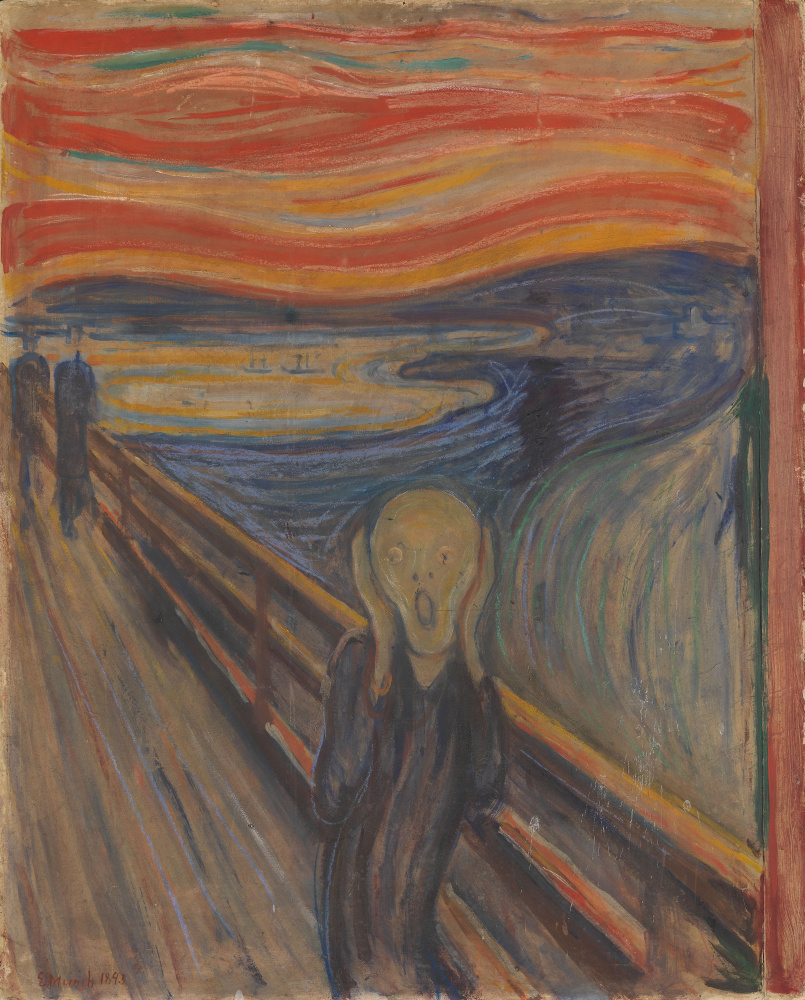

8. Scream by Edvard Munch, ca. 1893

Scream

1893, 91×73.5 cm

While William Ascroft worked heavily on creating a 500-sheet climatological archive of the skies in Britain, Edvard Much (1863−1944) in Oslo has just being conceiving the plot of the one of the world’s best-known paintings, The Scream. He also saw the strange and lurid Krakatoa sunsets while they happened. And they have haunted him up until 1893 when he finally painted them as he remembered.

This is how Munch described the sunset he witnessed after Krakatoa:

"I was walking along the road with two friends — then the sun set — all at once the sky became blood red — and I felt overcome with melancholy. I stood still and leaned against the railing, dead tired — clouds like blood and tongues of fire hung above the blue-black fjord and the city. My friends went on, and I stood alone, trembling with anxiety. I felt a great, unending scream piercing through nature."

He created several versions of The Scream which now are the most famous Expressionist masterpieces. All of them reflect his vision of human fear writhing beneath an apocalyptic sky, as "a great unending scream pierces through nature."

Scientists think that the Krakatoa eruption was accompanied by the loudest sound ever recorded, travelling almost 5,000 km, and heard over nearly a tenth of the earth’s surface. It was a great scream indeed.

This is how Munch described the sunset he witnessed after Krakatoa:

"I was walking along the road with two friends — then the sun set — all at once the sky became blood red — and I felt overcome with melancholy. I stood still and leaned against the railing, dead tired — clouds like blood and tongues of fire hung above the blue-black fjord and the city. My friends went on, and I stood alone, trembling with anxiety. I felt a great, unending scream piercing through nature."

He created several versions of The Scream which now are the most famous Expressionist masterpieces. All of them reflect his vision of human fear writhing beneath an apocalyptic sky, as "a great unending scream pierces through nature."

Scientists think that the Krakatoa eruption was accompanied by the loudest sound ever recorded, travelling almost 5,000 km, and heard over nearly a tenth of the earth’s surface. It was a great scream indeed.

9. Tornado over Kansas by John Steuart Curry, 1929

Tornado over Kansas

1929

John Steuart Curry (1897−1946), a native of Kansas, won prominence with his melodramatic and even anecdotal portrayals of the American life in regions where he lived. He is recognized as a prominent member of the artistic movement known as Regionalism.

Every native of Kansas knows of the uncontrollable destructive force tornado has at its disposal. It’s like a symbol of the weather’s power over life in the Midwest and over its farms in particular. The funnels of the violent storm evoke deep human fear and sense of dread. A widow of the artist claimed that Curry has never seen a tornado himself, but he definitely heard numerous stories about devastating tornados and saw its photographs.

Tornado over Kansas has been celebrated as soon as it was first exhibited. It received the second award at the "Century of Progress" display in 1930. Shortly after its debut, it appeared in school textbooks, art magazines, art history texts, and the Hollywood blockbuster Twister. The US nation saw it first in 1934, in the pages of Time magazine, where the painting was printed in an article about the new U.S. style painters. In 1935, the Muskegon Museum of Art acquired the canvas, which became one of the great icons of American Regionalism .

Every native of Kansas knows of the uncontrollable destructive force tornado has at its disposal. It’s like a symbol of the weather’s power over life in the Midwest and over its farms in particular. The funnels of the violent storm evoke deep human fear and sense of dread. A widow of the artist claimed that Curry has never seen a tornado himself, but he definitely heard numerous stories about devastating tornados and saw its photographs.

Tornado over Kansas has been celebrated as soon as it was first exhibited. It received the second award at the "Century of Progress" display in 1930. Shortly after its debut, it appeared in school textbooks, art magazines, art history texts, and the Hollywood blockbuster Twister. The US nation saw it first in 1934, in the pages of Time magazine, where the painting was printed in an article about the new U.S. style painters. In 1935, the Muskegon Museum of Art acquired the canvas, which became one of the great icons of American Regionalism .

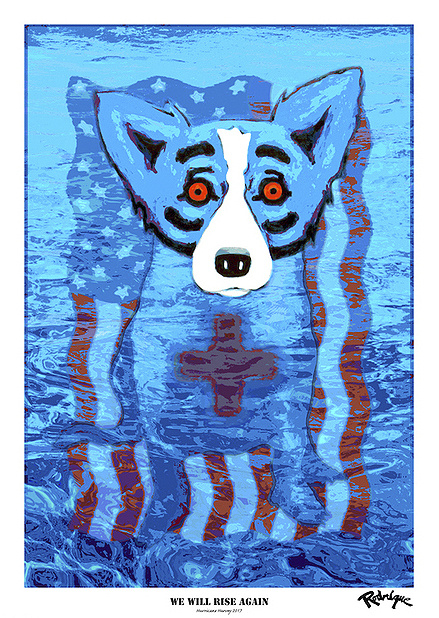

10. We Will Rise Again by George Rodrigue, 2005

We Will Rise Again

2005, 69×46 cm

In 2005, shortly after Hurricane Katrina and its accompanying floods, the famous American artist George Rodrigue (1944−2013) made his Blue Dog painting showing the blue canine with a red cross on its chest, floating on an American flag in a sea of water.

Back in 2005 Rodrigue described his painting and explained, "We Will Rise Again shows the American flag covered with water. The blue dog is partly submerged, and its eyes, normally yellow, are red with a broken heart. Like a ship’s SOS, the red cross on the dog’s chest calls out for help."

A price set by Rodrigue for the original 2005 post-Katrina edition of We Will Rise Again silkscreen prints was $500 each and the sales have raised $700,000 for disaster relief, according to the George Rodrigue Foundation of the Arts (GRFA). The GRFA and the Rodrigue family recently announced that they are re-releasing We Will Rise Again in a 2017 edition to benefit schools in Texas and Louisiana that have been damaged by Hurricane Harvey from August 25th to September 2nd, 2017.

This special release includes the reference "Hurricane Harvey 2017" in the white border alongside the words "We Will Rise Again" and Rodrigue’s official estate-stamped signature.

George Rodrigue, himself a survivor of many hurricanes, transformed the image of the Blue Dog, originated as a Cajun werewolf dog—The Loup-Garou, which is often used to scare children when misbehaving—into an international pop icon. This image brought him fame and helped many survivors to rise after Hurricane Katrina.

Back in 2005 Rodrigue described his painting and explained, "We Will Rise Again shows the American flag covered with water. The blue dog is partly submerged, and its eyes, normally yellow, are red with a broken heart. Like a ship’s SOS, the red cross on the dog’s chest calls out for help."

A price set by Rodrigue for the original 2005 post-Katrina edition of We Will Rise Again silkscreen prints was $500 each and the sales have raised $700,000 for disaster relief, according to the George Rodrigue Foundation of the Arts (GRFA). The GRFA and the Rodrigue family recently announced that they are re-releasing We Will Rise Again in a 2017 edition to benefit schools in Texas and Louisiana that have been damaged by Hurricane Harvey from August 25th to September 2nd, 2017.

This special release includes the reference "Hurricane Harvey 2017" in the white border alongside the words "We Will Rise Again" and Rodrigue’s official estate-stamped signature.

George Rodrigue, himself a survivor of many hurricanes, transformed the image of the Blue Dog, originated as a Cajun werewolf dog—The Loup-Garou, which is often used to scare children when misbehaving—into an international pop icon. This image brought him fame and helped many survivors to rise after Hurricane Katrina.

Titile illustration: Hurricane, Bahamas (1898) by Winslow Homer. Watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper, 36.7×53.5 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Written by Natalia Korchina on materials of various websites including The Guardian, theculturetrip.com, rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com, publicdomainreview.org, wendyrodrigue.com, hyperallergic.com, the MET Museum, Muskegon Museum of Art, Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., winslow-homer.com.

Written by Natalia Korchina on materials of various websites including The Guardian, theculturetrip.com, rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com, publicdomainreview.org, wendyrodrigue.com, hyperallergic.com, the MET Museum, Muskegon Museum of Art, Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., winslow-homer.com.