Restorer's brush versus master's hand: controversial issues of painting conservation and restoration

Only experts know that when passing through the halls of museums and galleries exhibiting old painting, you will not see a single picture created before the 19th century that would have been well preserved in its original form without the intrusion of a conservator into it. Time is ruthless to anyone and anything including works of art. But should we see traces of its destruction or take the pleasure of seeing the newly bright colors of Old Masters restored by conservators? And where is this fine line between a master’s hand and a restorer’s brush? Let’s view several world famous canvases before and after restoration to get the point.

The Virgin and Child with St. Anne by Leonardo da Vinci

The 18-month-long restoration of "The Virgin and Child with St. Anne" (above) by Leonardo da Vinci resulted in a controversial outcome. Dull, faded hues were transformed into vivid browns and lapis lazuli that had viewers awestruck.Like the novel "The da Vinci Code," the restoration of Leonardo’s last work that the master laboured on for 20 years until his very death has been accompanied by a high-level intrigue worthy of a movie thriller.

The Louvre, where the painting is housed, has long being hesitant to clean the canvas because of the fears over how the solvents were affecting the sfumato, a painting technique that Leonardo mastered. After cleaning has eventually started in 2009, two of France’s top art experts — Jean-Pierre Cuzin and Segolene Bergeon Langle — resigned from the Louvre advisory committee responsible for the restoration. Some sources reported they were outraged that conservators were over-cleaning the work to a brightness Leonardo never intended.

However, when Bergeon Langle saw the final result, she was partly relieved and reassured on some aspects that bothered her. Yet, she notably criticized the decision to remove a white patch on the body of the infant Jesus, which she said was painted by Leonardo himself.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

1510, 168×112 cm

A real revelation was made by means of the infrared photography used to scan the canvas. The exhibit showed two pictures secretly hidden in the painting for hundreds of years. One was drawn by a left-handed artist, and is thought to be by Leonardo, who was himself left-handed. It is a depiction of the hatchings on a horse’s head, similar to that in the mural of "The Battle of Anghiari," the missing fresco by the master made in Florence, also known as "The Lost Leonardo."

We see that the restored canvas came out much lighter. Instead of the cloudy dark shades that prevailed before, after restoration the painting is dominated by bright colors, as if a shift from evening to a sunny daytime has happened. And although some experts claim that it is contratry to da Vinci’s vision, we will never know the truth because no pristine work by Leonardo has been left to compare today.

We see that the restored canvas came out much lighter. Instead of the cloudy dark shades that prevailed before, after restoration the painting is dominated by bright colors, as if a shift from evening to a sunny daytime has happened. And although some experts claim that it is contratry to da Vinci’s vision, we will never know the truth because no pristine work by Leonardo has been left to compare today.

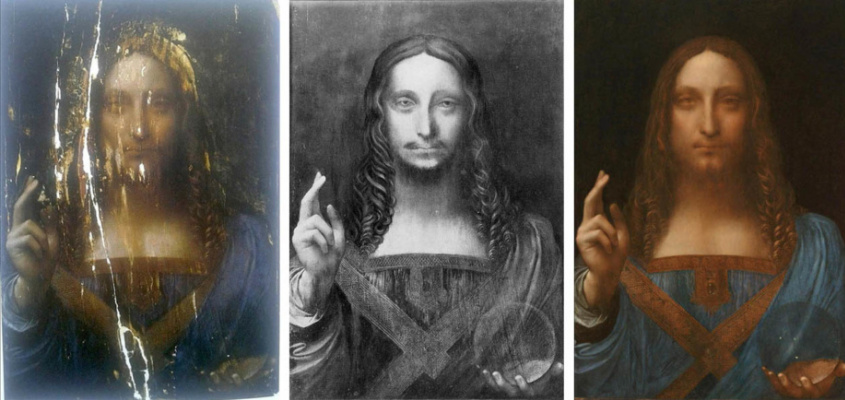

Salvator Mundi, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. 1. The removed overpainting reveals the image beneath it. 2. Overpainted version 3. The restored painting. Photos: credit to veronicasart.com

Salvator Mundi attributed to Leonardo da Vinci

New heated debates over the transparency of conservators' interventions into old paintings were reigned with the release of a pre-conservation image of Leonardo’s "Salvator Mundi" sold in November 2017 for $450m. The painting’s terrible condition and the quantity of restoration work done produced much doubts over the pureness of the da Vinci’s brush. The authorship, already doubted by many scholars, has been questioned even more after Christie released a pre-conservation image of Salvator Mundi, revealing big vertical cracks to the walnut panel and significant losses on its surface.Thomas Campbell, the former director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, prompted a flood of comments by posting the Christie’s image on Instagram with the caption "450 million dollars?! Hope the buyer understands conservation issues…" The Art Newspaper contributor, Bendor Grosvenor, responded to it with the phrase on Twitter suggesting that if Campbell had followed the work of the Met’s conservation department, "he would know that many Old Master paintings look like this, when stripped down".

What we see in the first image above is the removal of the historical overpainting done during 500 years since its creation that reveals the original painting underneath it. White lines look like preparatory ground (gesso) marks crudely painted over the cracks of the original painting trying to fill them in. In the central black and white image we see the poorly repaired wooden panel with the oil overpainting applied over the gesso made by restorers dozen of times prior to the last comprehensive restoration in 2007. The third image is the final result of the 2007 restoration undertaken by Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Senior Research Fellow and Conservator of the Kress Program in Paintings Conservation at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World)

1500, 65.7×45.7 cm

Whatever experts say, Dianne Modestini made an incredibly hard job cleaning and restoring the wooden panel. She opened Christ of Da Vinci from several layers of grease, dust and barbarian overpainting stripping the painting to its original state and fixing the "scratches." Moreover, she did not create a new version of the Savior like we see in the overpainted black and white image. Rather, Dianne restored the Da Vinci’s signature style — sfumato and the ethereal appearance of Christ’s face as it was rendered 500 years ago. We notice, however, that the original color of clothing varies remarkably. Probably it had even brighter blues of lapis lazuli in the beginning.

Would you be satisfied with viewing this work on a wall at the Louvre Abu Dhabi gallery prior to its restoration or you’d rather prefer it after being restored? The question is indeed a rhetoric one.

Would you be satisfied with viewing this work on a wall at the Louvre Abu Dhabi gallery prior to its restoration or you’d rather prefer it after being restored? The question is indeed a rhetoric one.

Rembrandt’s Danae before and after the most savage act of vandalism on a major painting in modern times. Photo: credit to kulturologia.ru.

Danae by Rembrandt van Rijn

"Danae" by Rembrandt housed at the Hermitage, Saint Petersburg, is the brightest example of an emergency care and the longest treatment that has ever been given by conservators and restorers to heal the disfigured wounds of a canvas.Regarded by common consent one of the most beautiful of all European paintings, Danae was irreversibly damaged by a vandal in the summer of 1985. A 48-year-old unemployed resident of Kaunas Bronius Maygis slashed the canvas with a knife twice. He cut Danae’s lower belly and a thigh but that wasn’t enough for him. He went on by pouring a sulphuric acid from a one-litre jar on the picture and shouted 'Freedom for Lithuania!' although Lithuanians themselves deny his political purposes. He has later been variously described as either ''a deviant,'' a madman or an embittered citizen of one of the Baltic republics.

Rembrandt’s Danae after the attack in 1985. Photo: credit to kulturologia.ru

A liter of sulfuric acid formed a dark, bubbling, foul-smelling mass that trickled down to the bottom of the frame

and from there onto the floor. As the attack happened on a weekend, no restorers were on the spot. First technical recommendations were made by two professors from the Institute of Technology only in an hour. They advised to keep the picture upright and, since no pumps or sprays were available, to pour, throw or, if necessary, spat small amounts of water on the damaged areas. This advice has later been contested by some professionals, on the grounds that the water may not so much have washed away the acid as caused it to spread. As a result, about 30 percent of the precious painting by Rembrandt was lost irrevocably.

Being first regarded as damaged beyond any hope of recovery, Danae, nonetheless, went back on view in the Hermitage in 1997 after 12 years of close and often perilous work on its restoration.

Being first regarded as damaged beyond any hope of recovery, Danae, nonetheless, went back on view in the Hermitage in 1997 after 12 years of close and often perilous work on its restoration.

The trio of highly professional restorers — Evgeny Gerasimov, Alexander Rahman and Gennady Shirokov, together with Tatyana Aleshina who provided scientific and methodical support — has accomplished all needed conservation works in a half of a year: stabilized the paint layer and the preparatory ground, made re-varnishing, and prepared a new duplicating canvas. Then they fought against the damaging paint trickles formed by acid and water on the surface for at least two more years. Eventually, the fundamental question came up: ''How far should the picture be restored? When was it time to call a halt?''

Above: Gennady Shirokov, Alexander Rahman and Gennady Shirokov working on Danae’s restoration, 1990-s. Photo: credit to kulturologia.ru.

The restorers were of the view that repainting would have made a counterfeit Rembrandt. They instead opted to fill in and retouch — making small transitions from one area to another. ''All the damaged areas had to be toned in, or touched in, to make a ground on which damaged areas could, if possible, be restored,'' said Mr. Gerasimov.

According to Evgeny Gerasimov, in the resulting painting, ''some parts are 100 percent Rembrandt, some are 50 percent Rembrandt, and some had to be redone. The left thigh is slightly restored. The right arm was 90 percent damaged but is now back to normal. The pearls were intact, but the jewels needed work. What the visitor sees is not 'the original,' and we would never put it forward as such. But the spirit of Rembrandt is intact.''

According to Evgeny Gerasimov, in the resulting painting, ''some parts are 100 percent Rembrandt, some are 50 percent Rembrandt, and some had to be redone. The left thigh is slightly restored. The right arm was 90 percent damaged but is now back to normal. The pearls were intact, but the jewels needed work. What the visitor sees is not 'the original,' and we would never put it forward as such. But the spirit of Rembrandt is intact.''

Danae

1636, 185×202.5 cm

Like the surgeons in a crisis medicine, the Hermitage conservators weighted all the risks and benefits to choose components that should be saved or sacrificed so that the painting would not lose the presence of Rembrandt. It’s obvious that when they returned integrity to scattered islets and points, they have lost the brightness of colors and chiaroscuros at some places. However, the forms, shades, proportions set by the master were preserved.

The restorers refused to repaint the transparent drapery that covered Danae’s legs. Their decision illustrates well the team’s approach to conservation and priorities in restoration. The cloth was literally washed away by the infernal solvent. Restorers were advised to recreate it. That wasn’t a problem for them as they were skilled painters. Nonetheless, they regarded the advice as nonsense: no one except for Rembrandt himself had the right to restore the lost cloth. They believed that they would better show the original depiction of the woman’s legs than overpaint it with their brush strokes.

Following the same principle, several small details were not repainted in Danae. For instance, a bundle of keys at an old woman’s right wrist behind Danae has completely dissolved in acid, but the detail was never restored again. The conservators decided not to make a replica over the original painting but preserve as much of a pristine Rembrandt as possible.

The restorers refused to repaint the transparent drapery that covered Danae’s legs. Their decision illustrates well the team’s approach to conservation and priorities in restoration. The cloth was literally washed away by the infernal solvent. Restorers were advised to recreate it. That wasn’t a problem for them as they were skilled painters. Nonetheless, they regarded the advice as nonsense: no one except for Rembrandt himself had the right to restore the lost cloth. They believed that they would better show the original depiction of the woman’s legs than overpaint it with their brush strokes.

Following the same principle, several small details were not repainted in Danae. For instance, a bundle of keys at an old woman’s right wrist behind Danae has completely dissolved in acid, but the detail was never restored again. The conservators decided not to make a replica over the original painting but preserve as much of a pristine Rembrandt as possible.

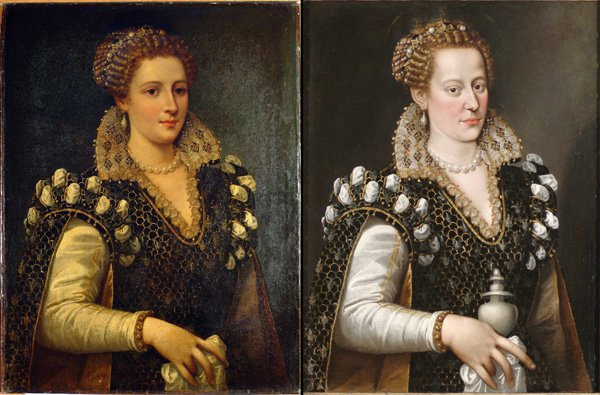

Pre- and post-restoration views of Isabella de' Cosimo I de Medici (circa 1570−74), attributed to Allesandro Allori. Photo courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.

Portrait of Isabella de’ Cosimo I de Medici attributed to Allesandro Allori

It is thanks only to restorers from the Carnegie Museum of Art that the portrait of Isabella de' Cosimo I de Medici (right) was discovered right beneath a portrait purported to be Eleanor of Toledo (left) and attributed to Bronzino. As it turned out, the depiction we have been viewing for 2 centuries or even more was actually a painted-over portrait of Eleonor’s scandalous daughter. Hidden and creatively repainted in the Victorian era, most likely to suit 19th-century tastes or to please some Victorian art-buyer, the revealed portrait is of much greater depth and shows much more interesting personality.The work accomplished by the restorers of the CMOA under a chief conservator Ellen Baxte is one of the most spectacular jobs ever done in paintings restoration and conservation. It was Lulu Lippincott, the CMOA’s curator of fine arts, who first suspected that the piece was no Old Master. She passed it along to Ellen Baxter, asking the conservation studio to confirm that it was a fake. Through inspection of paint crack-lines, and later X-radiographs, conservators determined that the original portrait of Isabella de' Medici had been creatively overpainted.

Ellen Baxter painstakingly removed layers of the newer paint, and slowly the original painting revealed a sterner face with a longer nose, jowls and a high plucked hairline. The Victorian-era overpainting changed the late Renaissance

aesthetics: Isabella de’Medici’s wrist had been thinned and her complexion warmed by a Victorian artist. In comparison with the original, the new overpainted portrait looked more like the artwork on a Victorian biscuit tin lid than the output of the Italian Mannerist.

The final breakthrough in the fascinating investigation came when Lippincott found a copy of the painting in a Florentine art history book. She learned that the portrait had been commissioned by the Medici family and sent to Vienna in the 1580s. What’s more, Mrs. Lippincott found out that the portrait was not of Eleanor of Toledo, but her daughter, the scandalous Isabella de’Medici, a beauty who was meant to maintain a strategic relationship with the powerful Rome-based family as a wife to Paolo Orsini. However, she was doomed to meet a violent end. After her beloved father died in 1574, her husband and her brother conspired to kill her after rumor reached Orsini in Rome that his wife had taken his own cousin as a lover.

Isabella did not move to Rome with her husband after the wedding as it was planned by her father. She rather preferred to establish herself in Florence, holding intellectual salons and being a patron of the arts. She spoke several languages and was known to be a lively and witty conversationalist. Some say she threw extravagant parties and allegedly had extramarital love affairs.

Lulu Lippincott and Ellen Baxter believe that, posing for the portrait, Isabella de’Medici was holding an urn similar to the one Mary Magdalane used to wash Jesus’s feet. She posed with it in an attempt to restore her reputation. "This is literally the bad girl seeing the light," Lippincott told Carnegie Magazine.

"Now that we have the picture as close to its original appearance as we can, scholars will be able to make an accurate assessment of its quality and authenticity," Lippincott said in 2014. She considered the painter was someone in Allori’s circle, or he himself, as the artist was the leading Medici court painter during the 1560s and 70s.

Isabella did not move to Rome with her husband after the wedding as it was planned by her father. She rather preferred to establish herself in Florence, holding intellectual salons and being a patron of the arts. She spoke several languages and was known to be a lively and witty conversationalist. Some say she threw extravagant parties and allegedly had extramarital love affairs.

Lulu Lippincott and Ellen Baxter believe that, posing for the portrait, Isabella de’Medici was holding an urn similar to the one Mary Magdalane used to wash Jesus’s feet. She posed with it in an attempt to restore her reputation. "This is literally the bad girl seeing the light," Lippincott told Carnegie Magazine.

"Now that we have the picture as close to its original appearance as we can, scholars will be able to make an accurate assessment of its quality and authenticity," Lippincott said in 2014. She considered the painter was someone in Allori’s circle, or he himself, as the artist was the leading Medici court painter during the 1560s and 70s.

Isabella de' Medici turned out to be less glamorous than she was before restoration, but now she’s authentic like a photo of a real girl without photoshop and filters.

Written on materials of theartnewspaper.com, the telegraph, veronicasart.com, kulturologia.ru, kommersant.ru, the new york times, art net news, the daily mail, carnegie museum of art. Title illustration: pre- and post- restoration images of The Virgin and Child with St. Anne by Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1508, oil on wood, 168 cm x 112 cm, the Louvre, Paris.