You can’t imagine the amount of harsh criticism being fired at the works of an immigrant from Tsarist Russia, who became one of the most famous American artists. "A daub", "a work of a house painter, not an artist", "the emperor has no clothes" - the more collectors pay for Rothko’s paintings, the more there are those willing to express their disappointment in them. We aren’t going to explain why Mark Rothko's paintings are so expensive, now we are driven by immodest ambitions to tell about their artistic value.

First of all, his artworks are beautiful (just don't tell Rothko about it)

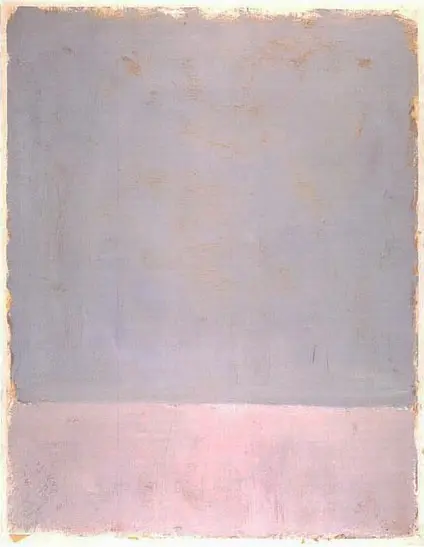

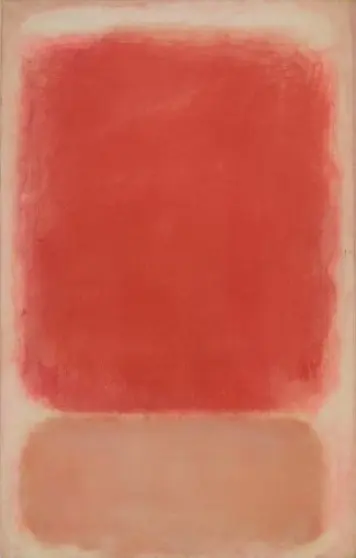

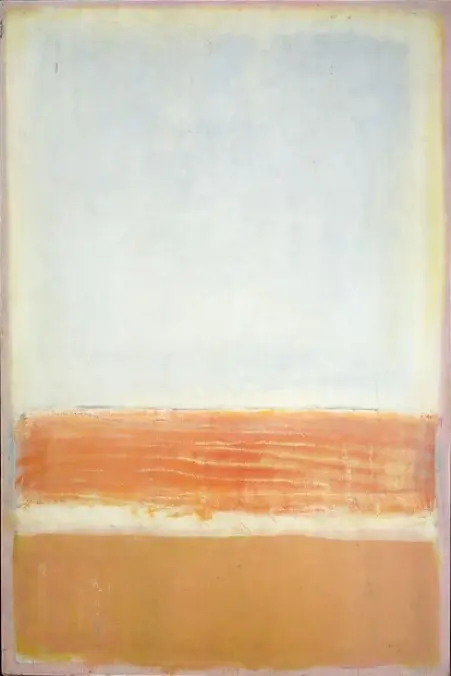

No matter how much effort the artist put into making the public perceive his paintings solely as the embodiment of pure, unalloyed emotions on canvas, he could not avoid the fact that they ideally fit into the bright, and sometimes strident interiors of their time.Although his rebellious brain was more excited by ideas and their adequate implementation than by how appealing his paintings would be to the viewer from an aesthetic point of view, Rothko created stunningly beautiful canvases. Whether he wanted to or not, he managed to find combinations of shades that are valuable on their own, in their minimalism and purity, regardless of the meaning that he put into them.

He was a gifted colourist, although for the artist it was more an insult rather than a compliment. This is evidenced by an incredible story, which, it seems, could only happen to him.

The list of honored guests invited to the inauguration of President Kennedy in 1961 included Mark Rothko. He considered it an honor, but exactly until the moment when Kennedy’s sister and her husband asked the artist to bring one of his works in order to estimate how much it would fit the style of their apartment. That was enough for Rothko to cut off all contact with the Kennedy family forever.

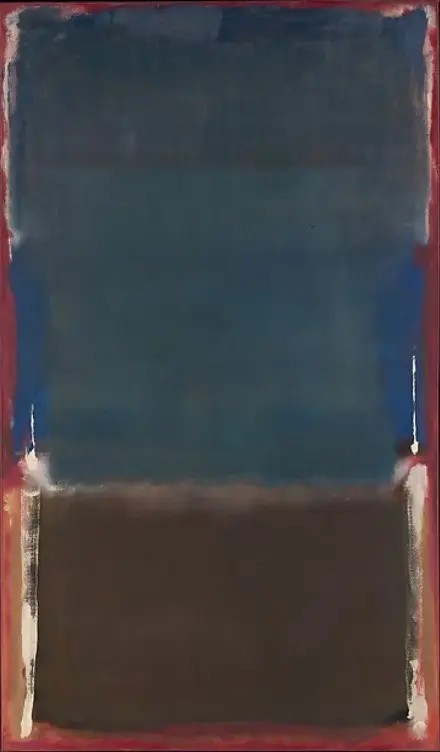

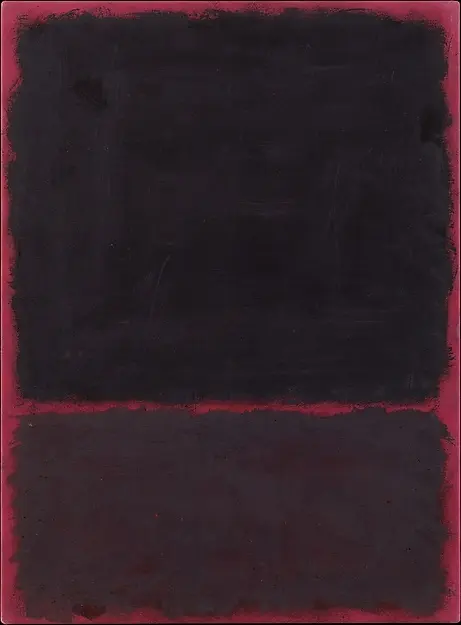

And this is not the only case when the artist didn’t want to give his paintings, regardless of the prestige of his potential client or a fat paycheck. The realization that his paintings were valued by the admirers primarily in terms of their decorative function was extremely painful. So in the second half of the 1950s, Rothko began deliberately laying it on thick, choosing darker shades. But it didn’t really help: his artworks were still painfully beautiful.

The list of honored guests invited to the inauguration of President Kennedy in 1961 included Mark Rothko. He considered it an honor, but exactly until the moment when Kennedy’s sister and her husband asked the artist to bring one of his works in order to estimate how much it would fit the style of their apartment. That was enough for Rothko to cut off all contact with the Kennedy family forever.

And this is not the only case when the artist didn’t want to give his paintings, regardless of the prestige of his potential client or a fat paycheck. The realization that his paintings were valued by the admirers primarily in terms of their decorative function was extremely painful. So in the second half of the 1950s, Rothko began deliberately laying it on thick, choosing darker shades. But it didn’t really help: his artworks were still painfully beautiful.

Genius is in the details

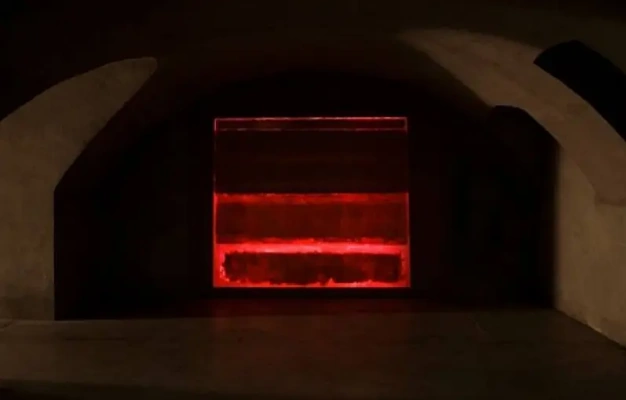

Indeed, Rothko’s paintings were more than just paintings. And in a way, they were even more than art. He lived them and wanted the viewers to fully immerse themselves in the space of his canvases. For the sake of this goal, he had no room for compromise when it came to their presentation.Galleries had to comply with all his requirements. Walk-through halls were not suitable for Rothko’s paintings. Moreover, there had to be no works by other artists or any foreign objects: nothing could prevent viewers from positioning themselves in direct contact with Rothko’s artwork. Therefore, there had to be minimal lighting, closed windows and no frames — nothing that could shift the focus from the canvases themselves.

The artist would definitely like the placement of his painting Four Darks in Red in Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Photo: restbee.ru

At the peak of his creative powers, Rothko was no longer thinking in categories of individual canvases, his mind came up with the concepts of inseparable art space. He sought to create whole ensembles that would sound in harmony with the vibrations of his feelings. Rothko’s ultimate dream was to create paintings, conceived for specific rooms, ideally designed by him — with the necessary geometry of the walls and placement of sources of natural light.

"A picture lives by companionship, expanding and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer. It dies by the same token. It is therefore risky to send it out into the world. How often it must be impaired by the eyes of the unfeeling and the cruelty of the impotent who would extend their infliction universally," believed the artist.

Rothko – the most specific of the abstract ones

Painting began separating from its decorative, religious or imprinting transient moments of life function long before Rothko started practicing it. Over time, more artists have been trying to use their works to tell the viewer something rather than showing it. In our century, technique, skill, or virtuosity of performance are not so important, it’s more about ideas and meanings now.Rothko freed his paintings from these bonds: he was annoyed by any of their interpretations or discerning hidden messages — in this respect he was extremely straightforward. "The tragic experience of catharsis is the only source of any art. Art is an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by those willing to take risks," he wrote.

Those were the viewers who were Rothko’s main critics and judges, whose opinion was decisive for him, unlike the verdicts of any authoritative sources. The artist said: "No possible set of notes can explain our paintings. Their explanation must come out of a consummated experience between picture and onlooker. The appreciation of art is a true marriage of minds. And in art as in marriage, lack of consummation is grounds for annulment."

Paintings of 1946−1948, in which Mark Rothko’s signature style began to be more pronounced.

Despite the fact that today the artist is considered one of the leading representatives of abstract expressionism

, he did not consider himself to be one. And the more popularity he gained, the more it seemed to him that critics, admiring his "abstractions", were missing the point.

Mark Rothko declared: "My art is not abstract; it lives and breathes. I’m not interested in the relationship of colour and form or something in this spirit. I’m interested only in expressing the basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, despair. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate these basic human emotions."

Mark Rothko declared: "My art is not abstract; it lives and breathes. I’m not interested in the relationship of colour and form or something in this spirit. I’m interested only in expressing the basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, despair. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate these basic human emotions."

The rest is a matter of technique

Like in other fields of art, recognizability and the artist’s personal style is the most valuable thing a talent can possess in today’s world. There are millions of people with excellent voices in the world, but how many of them can we unmistakably identify when hearing them on the radio? We have a similar situation with painting.If you’ve seen a collection of Rothko’s canvases at least once, their image is sure to firmly ingrain in your mind. And they are unlikely to be mistaken for the works of other authors (unless they are the artist’s imitators).

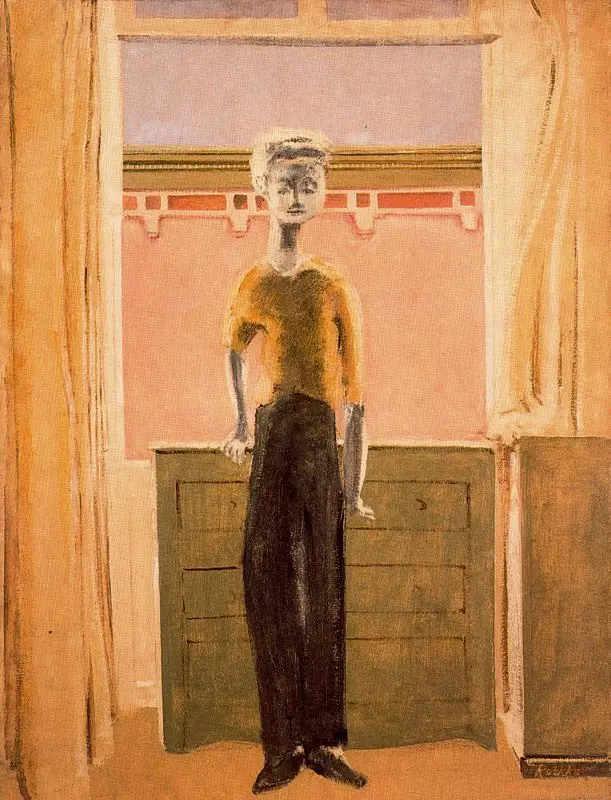

Those were Rothko’s experiments before he developed his signature style.

At least for the mercantile reason that collectors, driven by vanity, are historically inclined to buy works of art with clear authorship even without a signature in the lower corner, a unique style is half of the artist’s success.

Patterns based on the motifs of the works by van Gogh, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Dalí, Warhol and others are reproduced and replicated in the most unimaginable guises: from interior items to cups, clothes, cake designs and even hairstyles.

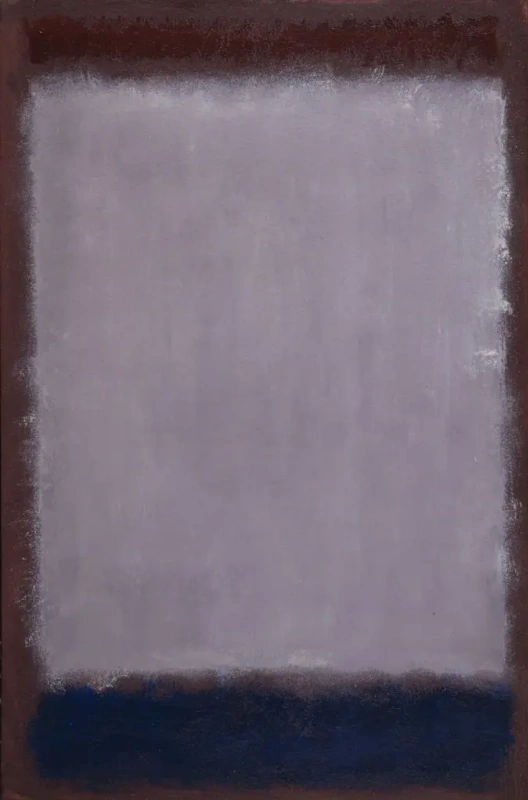

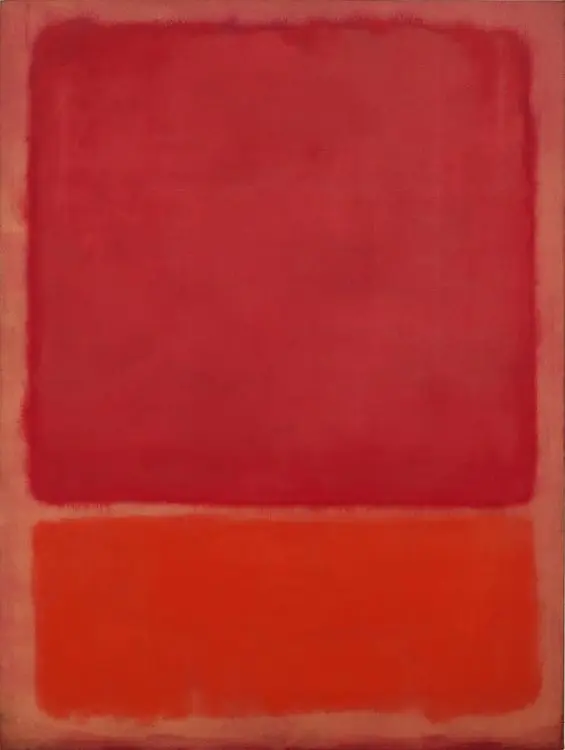

Rothko also managed to immortalize his name by inventing an unmistakably recognizable formula: rectangular shapes hovering on the subtly diffused canvas. But like Malevich’s squares, Rothko’s colour fields aren’t as simple as they seem. The artist used several techniques, the secret of which was hidden even from his assistants.

Patterns based on the motifs of the works by van Gogh, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Dalí, Warhol and others are reproduced and replicated in the most unimaginable guises: from interior items to cups, clothes, cake designs and even hairstyles.

Rothko also managed to immortalize his name by inventing an unmistakably recognizable formula: rectangular shapes hovering on the subtly diffused canvas. But like Malevich’s squares, Rothko’s colour fields aren’t as simple as they seem. The artist used several techniques, the secret of which was hidden even from his assistants.

Little known and unusual Rothko of the 1930s: subjects and elusive figurativeness were still on hand. As well as the coming forward dictatorship of geometry and colour.

Studies conducted with electron microscopy and ultraviolet radiation allowed to determine that the artist used natural ingredients like eggs or rabbit skin glue, as well as artificial substances: acrylic resins, phenol formaldehyde, modified alkyd, and others. He needed all this in order to make the paints dry quickly without mixing them, so that he could easily apply new layers on top of the old ones.

The number of such layers in some paintings could reach twenty, and the artist would often use similar shades, which allowed him to achieve the needed effect of depth and shimmering. Rothko also deliberately avoided any frames, both literally and figuratively: he even blurred the edges of his canvases, as if the space of the painting had no boundaries.

The number of such layers in some paintings could reach twenty, and the artist would often use similar shades, which allowed him to achieve the needed effect of depth and shimmering. Rothko also deliberately avoided any frames, both literally and figuratively: he even blurred the edges of his canvases, as if the space of the painting had no boundaries.

Mark Rothko in front of his painting No. 7, 1960 (Sezon Museum of Modern Art, Karuizawa, Japan).

Black square in a cube

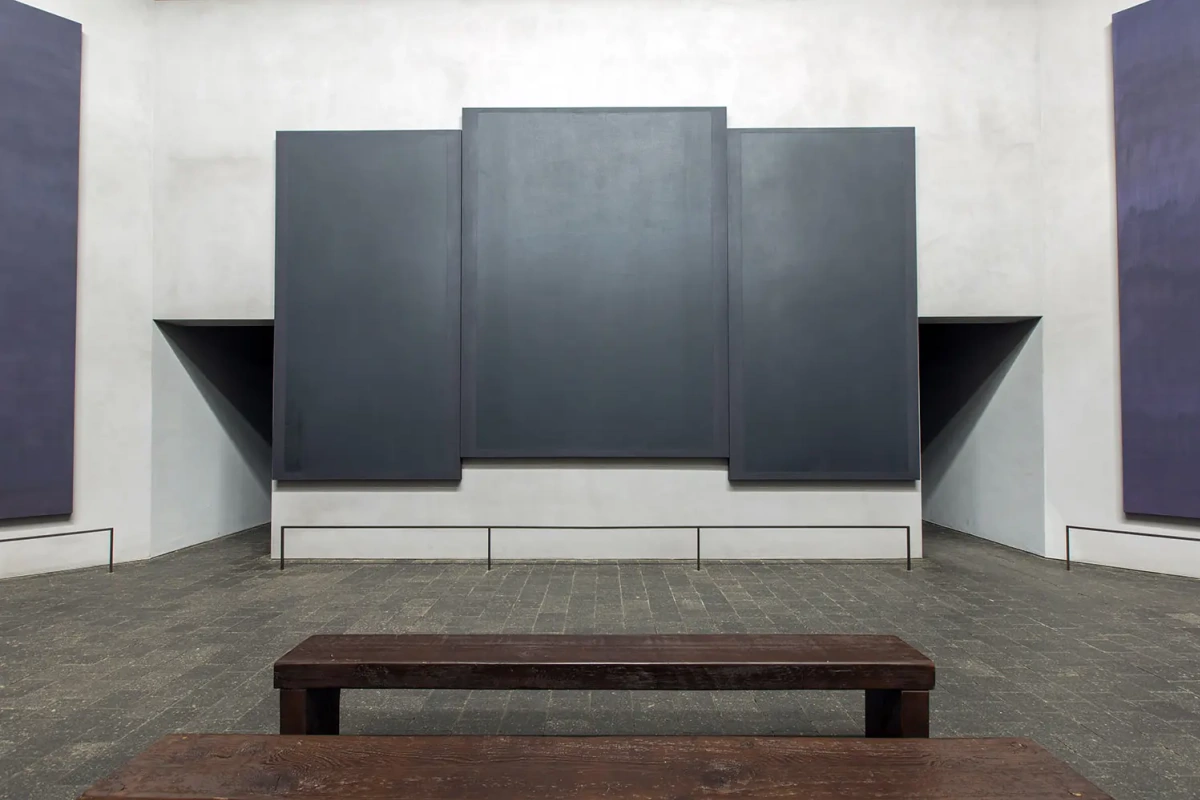

A religious building in Houston, Texas, better known as The Rothko Chapel, became the culmination of Rothko’s artistic evolution and, in some ways, his mausoleum. The artist’s work on the series of murals for the Four Seasons restaurant (which never appeared at their intended site — Rothko refused to have them exhibited at a restaurant so dedicated to the excessive consumption of capital) inspired a couple of oil barons de Menil to commission the artist to paint canvases for the chapel on the campus of the University of Saint Thomas.

Some of Rothko’s murals painted to decorate the restaurant in the Seagram Building are on permanent display in the 'Rothko Room' at Tate Modern, London. Photo: timeout.com

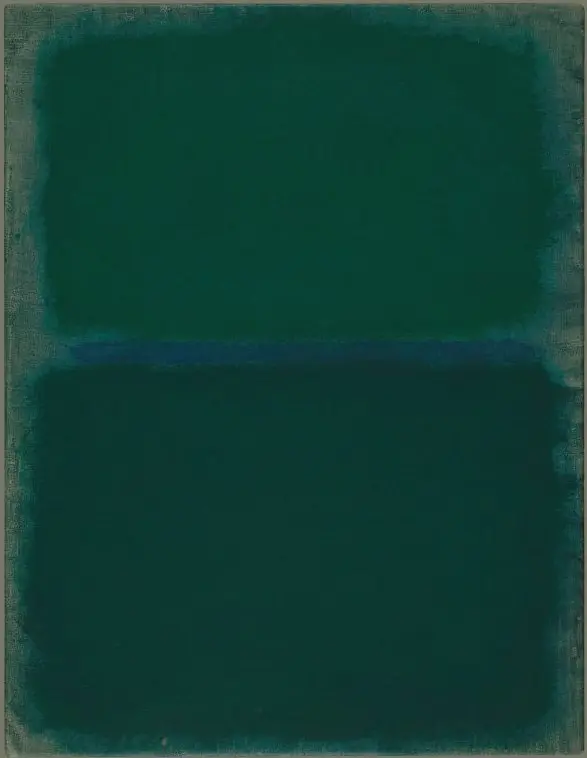

For the chapel, which was originally conceived as a Catholic one, and eventually has been shaped into an ecumenical center that offers a holistic experience (and equally — the art center), Rothko created 14 large-scale paintings. Seven of them are black rectangles, almost blending with vibrant burgundy background. Another seven canvases are painted in violet, reminiscent of shades of the night sky in different time of the day and under various weather conditions.

Photo: rothkochapel.org

Rothko spent three years (1964 — 1967), working on paintings for the chapel, and this was not without intrigue. The terms of the contract allowed the artist to have a say in the architectural layout of the building, which lead to the quarrel with the first architect who worked on the project. Then Rothko cooperated with two more architects, but did not live to see the end of the construction. And yet, it was on the request of the artist that the octagonal chapel has the vaulted ceiling which offers natural light to stream in.

Photo: rothkochapel.org

The Rothko Chapel was opened in 1971, a year after the artist’s death. And while some visitors look around in bewilderment, asking "where are the paintings?", others spend a long time in front of the meditative overflows of Rothko’s "black holes".

If in the process of working on his murals for the restaurant the artist wanted visitors to feel eternally walled up with brick walls, here, apparently, he offered the viewer to feel the maximum closeness to eternity. Either in zero gravity among the silence of outer space, or in the final resting place, when the last nail is hammered into the coffin.

As it often happens with the heritage of the artist, The Rothko Chapel also became a source of inspiration for other artists. For example, for Peter Gabriel, who wrote the song Fourteen Black Paintings, which was included in his sixth studio album Us in 1992.

If in the process of working on his murals for the restaurant the artist wanted visitors to feel eternally walled up with brick walls, here, apparently, he offered the viewer to feel the maximum closeness to eternity. Either in zero gravity among the silence of outer space, or in the final resting place, when the last nail is hammered into the coffin.

As it often happens with the heritage of the artist, The Rothko Chapel also became a source of inspiration for other artists. For example, for Peter Gabriel, who wrote the song Fourteen Black Paintings, which was included in his sixth studio album Us in 1992.

The Broken Obelisk in front of The Rothko Chapel is a sculpture by Barnett Newman, the artist’s ally in colour field painting. Photo: rothkochapel.org

Cover illustration: Mark Rothko. White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose), fragment. 1961

Author: Natalia Azarenko

Author: Natalia Azarenko

Artistes mentionnés dans l'article