The noble dancer

Cléopatra was born in Paris in 1875. Her father Carl (also Karl) Freiherr von Mérode (1853−1909), by the way, was a famous landscape painter. Thanks to her mom, the girl entered the Paris Opera ballet school at the age of seven and started performing at the Grand Opera shortly after. Malicious gossip had it that Cléo owed her brilliant career not to the choreographic skills, but only to her wondrous beauty. We can’t confirm anything here — what is known is only that Cléo's career was fostered by her mother, a strong-willed woman.

At the age of 23, Cléo took up a solo career and performed on the stages of the Royal Theaters of France, had sold-out shows at the Folies Bergère and went on tours in Europe and America. The peak of her popularity was in the 1900s and 1910s, but even after she officially left the stage in 1924, the dancer occasionally performed at special invitations of entrepreneurs at the age of 50, which is a rare case for a ballerina.

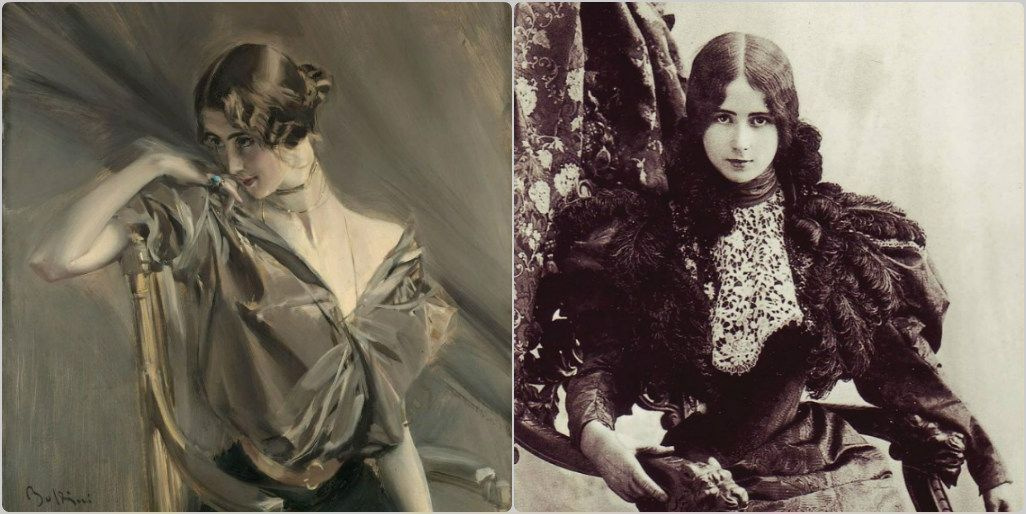

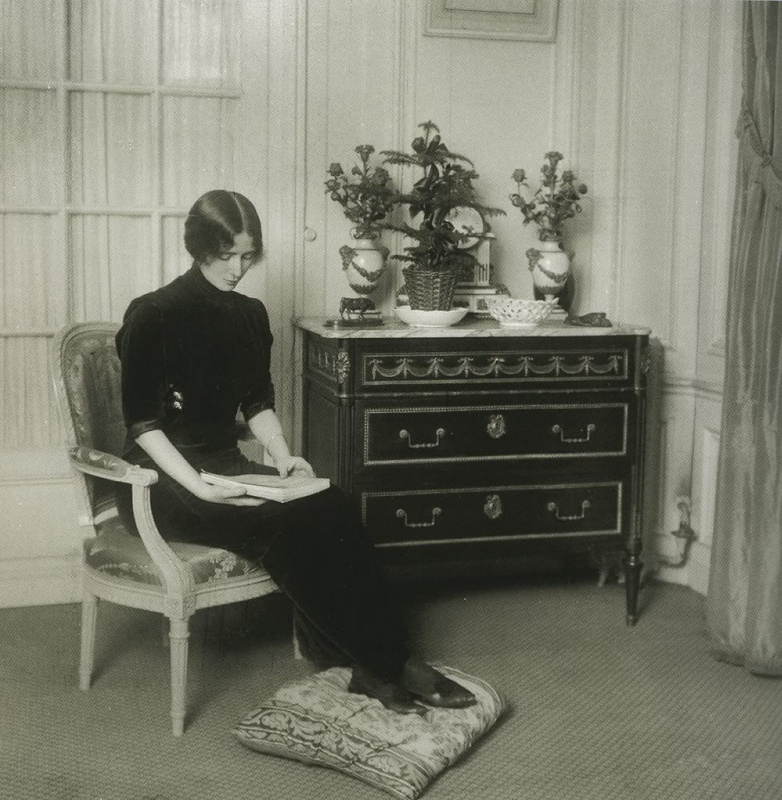

In the photo — Cléo de Mérode

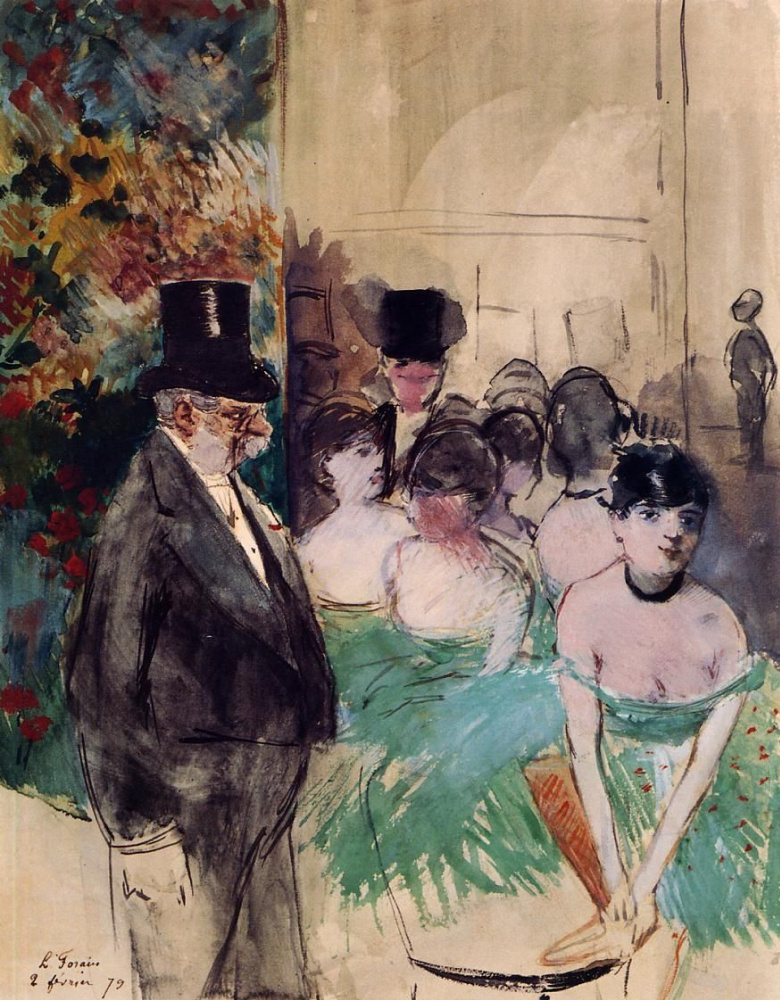

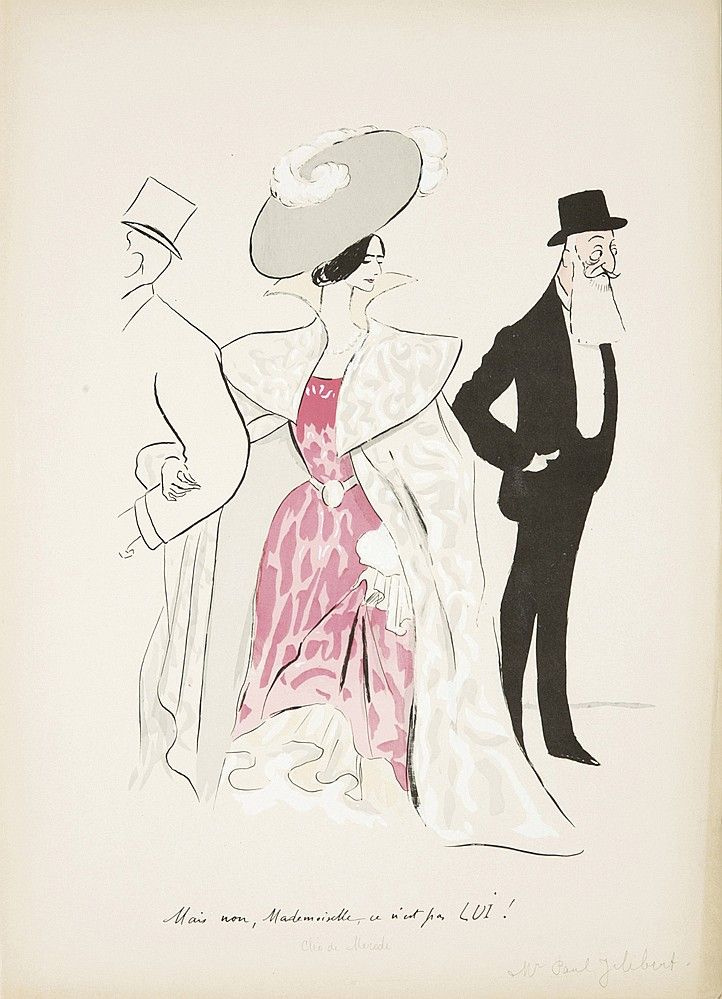

Dancers, ballerinas, cabaret singers and circus performers who openly showed their bodies on stage were considered courtesans. 12−16-year-old girls attending the ballet school were called small mice (petites rats). Only the richest and most powerful gentlemen could go see those young vestals in the temple of debauchery — the "national harem" or "a sanctuary for Venus’s progeny," as the Opera’s foyer was called, which caused many rumours, caricatures and obscene jokes.

Jean-Louis Forain, The Admirer

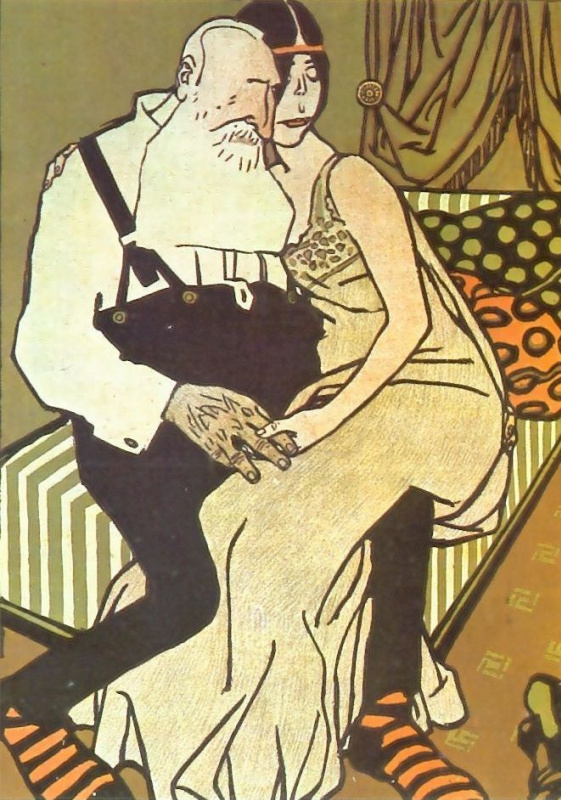

An overlord at the feet of a beautiful ballerina

Many attributed to them a torrid love affair, although the dancer herself claimed all her life that there was nothing between them — except an impressive bouquet of roses presented to her after one of the performances.

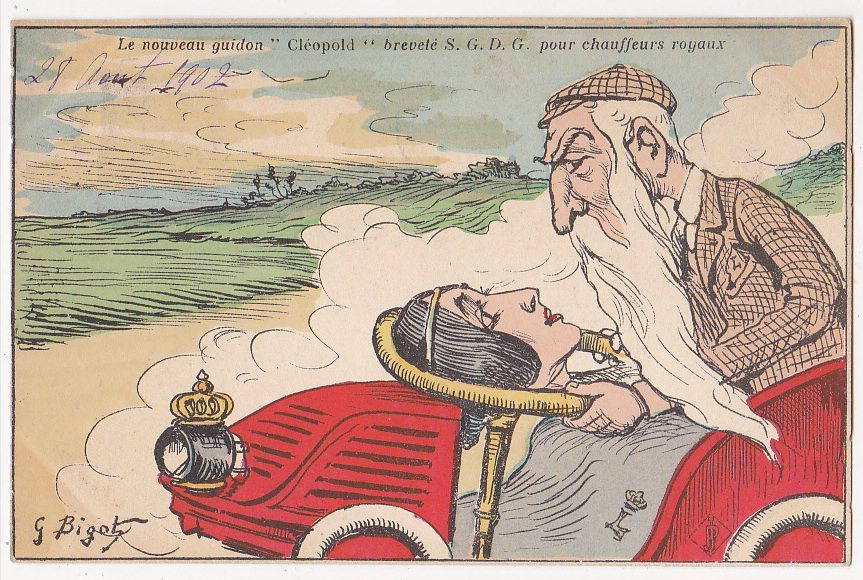

Despite all Cléo's attempts to protect her fair name, she was still known as the king’s mistress. The Parisians called the monarch Cléopold, and in the press, there appeared more and more new caricatures, competing in sharpness and not always propriety.

But of all the rumours, the most valuable for us is… the metro! They say that the king decided to make a valuable gift to France, and it was Cléo who suggested financing the construction of the metro. It was really built with the money of the Belgian monarch and opened in 1900.

The beauty of all beauties – a hostage of her own fairness

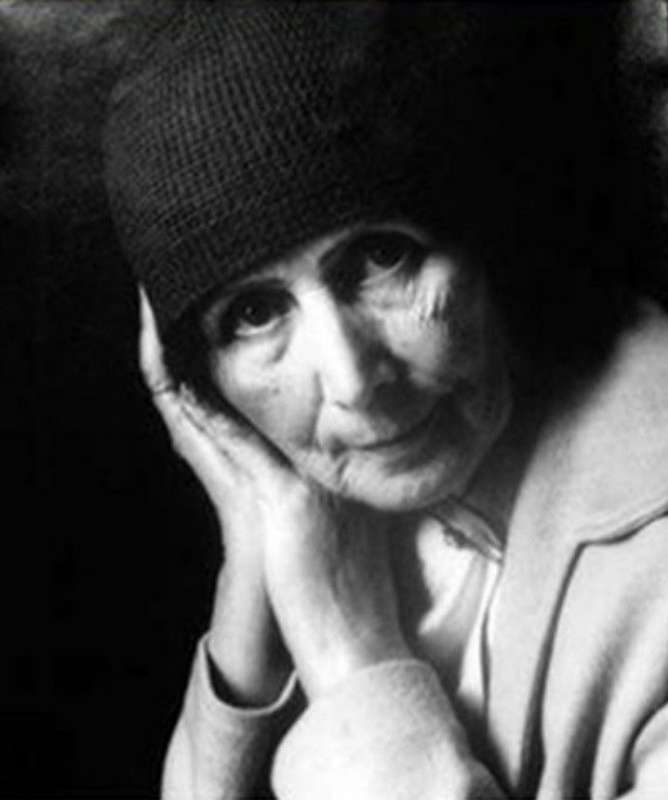

Gossip and slander haunted this beautiful woman all her life. In 1952, the year of publishing Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Second Sex, in which Cléo was called a "demi-mondaine," the ballerina just had enough. She went to court to protect her honour and won the case. In 1955, the ballerina published her memoirs Le Ballet de ma vie (The Dance of My Life).

The first photo-model

The development of photography made Cléo's image popular all over the world. The most famous studios for photographic portraits in Paris — those of Paul and Félix Nadar and Léopold-Émile Reutlinger — experimented with Cléo's image. She appeared on the postcards as a fashionable socialite, a charming dancer, and even in a prayer pose that suited her angelic appearance. Cléo eagerly posed for fashion magazines, which made her known as one of the first professional photo-models.

The "impossible" outfits of the fashion icon

Among other things, Cléo was a sharp dresser. Nowadays, her stunning outfits can be seen at The Palais Galliera — a fashion museum in Paris.

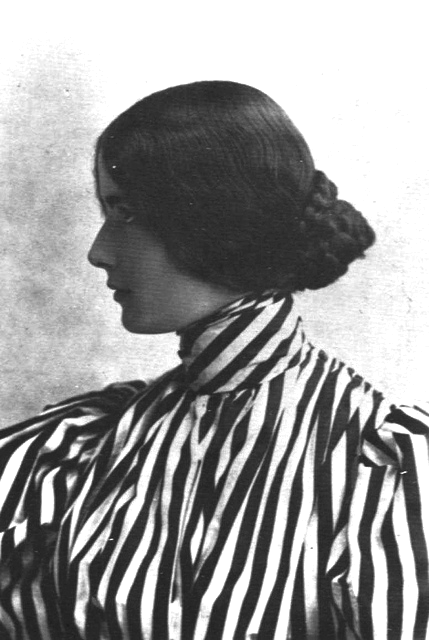

What’s more, Cléo came up with a new hairstyle. Have you noticed the way her hair is done in all the photographs, paintings and sculptures? Parted in the middle, covering her ears and put in a low bun. Not only all European women of fashion of the beginning of the 20th century, but also the characters of the works by Maugham and Fitzgerald styled their hair that way.

Photo by Nadar

Cléo de Mérode died in 1966 at the age of 91. There is a statue of the dancer that decorates her gravestone in Paris. The author of the work is a marquis, a Spanish diplomat who worked at the Embassy in Paris and amateur sculptor Louis de Périnat. Louis was the only known lover of Cléo, who kept her personal life secret. They were dating back in 1906−1919. In 1909, Louis created a portrait of his beloved woman.

Photo of Cléo de Mérode